I need a few more days to fully come to terms with Midsommar before I write about it, and the thing I’ve been planning to write for a while about the films of Claire Denis isn’t all the way there yet, so in the interim I’m gonna rank some stuff. Namely, (most of) the filmography of one of my absolute favorite filmmakers: Martin Scorsese. When I say most of, I mean I haven’t seen all of his films. The ones that will not be appearing on this list are- Who’s That Knocking at my Door, Boxcar Bertha, Alice Doesn’t Live here Anymore, New York, New York, The Color of Money, The Last Temptation of Christ, The Age of Innocence, Kundun, Bringing Out the Dead, The Aviator, and Silence. Which, now that I write it all out, seems like too much to leave out. But I’ve already written all this, so away we go. Also, only narrative feature films. So no New York Stories, Shine a Light, The Rolling Thunder Revue, The Last Waltz, etc. This list will be updated as I watch more of Scorsese’s films. Anyway for real now let’s go.

Honorable mention- Quiz Show

I’d like to use this opportunity as a reminder of two things- Martin Scorsese is in Quiz Show, and Quiz Show rules. I promise the list is about to start.

14- Casino (1995)

Blech. I don’t understand what people love about this movie. I mean, it has its moments. Joe Pesci’s narration cutting out mid-sentence because of his character’s death is straight-up brilliant. The blueberries scene is good. There’s a Saul Bass title sequence. And that’s it. Casino isn’t exactly a Goodfellas retread, but it isn’t not. Everything great about Goodfellas is duller and more mediocre here. The narration is overdone. De Niro is more subdued, less dynamic. Pesci is playing the same character but… less. It’s just less than Goodfellas. It’s also too long and weirdly boring. It’s like a predictive text Scorsese movie, and that’s not a good thing.

13- Hugo (2011)

I gotta be honest- I don’t really remember this one. Which, while it’s true that I saw it when I was very young, probably isn’t that good. What I do remember isn’t spectacular. The feeling I got kinda reminds me now of a 2010s Spielberg movie- not bad by any measure, but really unremarkable (shoutout to Bridge of Spies, however, that movie owns). It gets a pass over Casino because Casino sucks. Hugo, in my memory, is unremarkable at worst. Everything above here is phenomenal, so there’s nowhere else it could’ve been.

12- The King of Comedy (1983)

11 out of the 13 films on this list are masterpieces, this one is just the least amazing. It’s De Niro’s best against-type performance, and the story remains extremely relevant. The King of Comedy was what Scorsese settled on when De Niro expressed his desire to do a lighter film, after the two had collaborated on Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, and Raging Bull, among other things. The King of Comedy is as dark as any of them. But much funnier.

11- Cape Fear (1991)

Robert De Niro being one of the greatest actors in the history of film is a common theme on this list (part of why Casino is so bad is because his performance really isn’t that good). But taking on a role made iconic by Robert Mitchum, another of history’s greatest actors and improving on it (I won’t get into that now but there’s an argument to be made either way)? That’s an achievement on an impressive level. De Niro’s tour de force here powers Cape Fear to the status of one of the greatest remakes of a classic film ever, but the film succeeds for other reasons too. Nick Nolte is fantastic, and the neo-noir atmosphere is just so much fun. It’s a perfect follow-up to Goodfellas– scaled down and not trying to top it. And in doing so, it creates something of its own, something fantastic and brilliant.

10- Gangs of New York (2002)

We interrupt this Robert De Niro appreciation-fest to bring you Daniel Day-Lewis. Day-Lewis dominates the film so much as the diabolical gangster Bill “the butcher” Cutting that he received an oscar nomination for Best Lead Actor (it’s totally a supporting role. A big one, but still a supporting one). It’s a career highlight that clearly laid the groundwork for his absolute best role in There Will be Blood. Outside of Day-Lewis, there’s still a lot in this one. Gangs is an epic film that was the start of Scorsese’s collaboration with Leonardo DiCaprio. It also features turns from Cameron Diaz, John C. Reilly, Liam Neeson, and Brendan Gleeson, all of whom are various degrees of great. It’s visually brilliant, which is even more impressive when you find out that there’s exactly one piece of CGI: the elephant (which they wanted to do practically!). At its worst, Gangs of New York drags a little. At its best, it’s a masterwork, an odyssey of redemption and honor that serves as maybe the most integral part of Scorsese’s chronicles of New York besides Taxi Driver. Scorsese is the best New York filmmaker, by the way. Sorry Woody Allen. Also, Gangs of New York is one of the most nominated films in oscar history to not receive a single award (It had 10 nods. True Grit in 2010 and American Hustle in 2013 also had 10, while the record is shared by The Turning Point in 1977 and The Color Purple in 1985).

9- Shutter Island (2010)

Mysterious, eerie, and dark as hell, this period stunner wouldn’t work as well as it does in the hands of a lesser filmmaker. While Scorsese’s films aren’t typically this genre-specific, he kills it with this one. Gorgeously shot by Tarantino regular Robert Richardson, Shutter Island is entirely atmospheric. And WOW what an atmosphere. I first saw this one knowing nothing about it except that it was directed by Scorsese and it had a great twist (it does). I wasn’t expecting the masterpiece of a slow burn thriller I proceeded to experience. It was after watching this that I first realized that DiCaprio is one of the greatest actors of all time (this was before having seen The Wolf of Wall Street and The Revenant). Mark Ruffalo is great as usual, as is Ben Kingsley. And MAX VON SYDOW is in it. It’s a perfect movie. Also, it’s almost a shame to mention this because it takes away from what a gloriously brilliant achievement the film is, but the twist is all-time. Up there with Fight Club and The Sixth Sense.

8- Mean Streets (1973)

Eighth place feels incredibly low for the movie that, in one scene, invented both movies and music. Seriously, watch it.

Oh, and also it was Martin Scorsese’s first commercial success and it launched the career of Robert De Niro. Richie Aprile from The Sopranos is in it. I’m not sure I have to say any more, but I’m gonna. It features a brilliant opening scene (below), one of Harvey Keitel’s greatest performance (although he is outdone by De Niro to the point that Scorsese replaced Keitel as his leading man in the next movie he did). It features brilliant examinations of some of Scorsese’s most important themes, such as masculinity and Catholic guilt. And it’s seventh on this list. That should tell you something.

7- After Hours (1985)

Is this the most underrated film of all time? Considering it’s directed by a legendary auteur and is solidly well-known, probably not, but it’s up there simply because it’s SO GOOD. The true essence of a midnight movie, this one works best when watched at night (In my experience, Eraserhead and Kill Bill are other great midnight movies, if you’re looking for recommendations). The brilliance of After Hours is that it’s absolutely nuts. Guy meets girl, guy goes to girl’s apartment to buy magnet, guy is wrongfully blamed for girl’s death, guy spends the night on the run, guy gets built into a sculpture that is then stolen. Not exactly a classic story. Directed by Scorsese, but you would never know it. He’s having fun here- you can see it in the camera angles (think the falling keys), in the general absurdity of the comedy, and in the fact that it’s focused on entertaining before making a broad statement about human nature. In this case, that isn’t a problem. There’s truly nothing like it.

6- The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

This list has been going through masterpieces since the 11 spot, but this is where it gets real. The Wolf of Wall Street is many things, which is only fitting because it’s a film that deals entirely in excess. The sex, the drugs, the length, the language (record for uses of “f**k” in a movie that isn’t about swearing), they all serve one purpose: to further the theme of excess. Jordan Belfort’s lifestyle isn’t presented this way by Scorsese just because, it’s to tell the story accurately. The story is one of American greed in its purest form. How quickly greed takes over and the kind of things it does to people. It’s like Goodfellas, if the violence were traded in for financial scams. Also, DiCaprio has never been as good and Jonah Hill is revelatory. The Wolf of Wall Street is a glorious, phenomenal sensory overload of a movie. One of the greatest films of the 2010s. And it only gets better from here.

5- The Irishman (2019)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65412061/irishman3.0.jpg)

Scorsese’s latest is clearly one of his masterpieces. It earns every second of its titanic length with brilliant performances across the board (Pacino is a god), masterful storytelling, and a brilliant commentary on human mortality. It’s a late-career work in every sense, but that doesn’t mean he’s slowed down. The Irishman could probably be ranked below Wolf of Wall Street, but it could also be one or even two spots higher. It’s a breathtaking feat of cinematic excellence, the kind of thing that Scorsese does far more often than he has any right to. Reviewed in greater depth here.

4- The Departed (2006)

*Insert depahted joke*. Now that that’s out of the way, let’s talk about this, my second favorite Scorsese movie. The plot is so genius, complex, and Scorsese-an that it’s crazy that Scorsese didn’t think of it (for those uninitiated, it’s a remake of Infernal Affairs, a 2002 Hong Kong film). With the combination of director and plot, the least The Departed could’ve been was only slightly great. Instead, it’s an all timer. Matt Damon and Leonardo DiCaprio are equally brilliant as the gangster inside the cops and the cop inside the mob, respectively. Mark Wahlberg is awesome. For real, the only other place the guy is this good is Boogie Nights (another of my favorite films. Huh.), and you could argue that he should’ve won the oscar for supporting actor over Alan Arkin for Little Miss Sunshine (but damn is Arkin great in that). But the true best performance goes to the one and only Jack Nicholson (this has become a rundown of the greatest actors ever. All that’s missing is Brando). Nicholson is so unbelievably entertaining, over the top, and just plain great. I’ve seen it said that he tanks the movie and isn’t good. To that I simply say no. It’s one of the best performances of his career, and I understand the gravity of that statement. Also, in the last like 20 minutes it devolves into a Shakespearean tragedy. Huge plus.

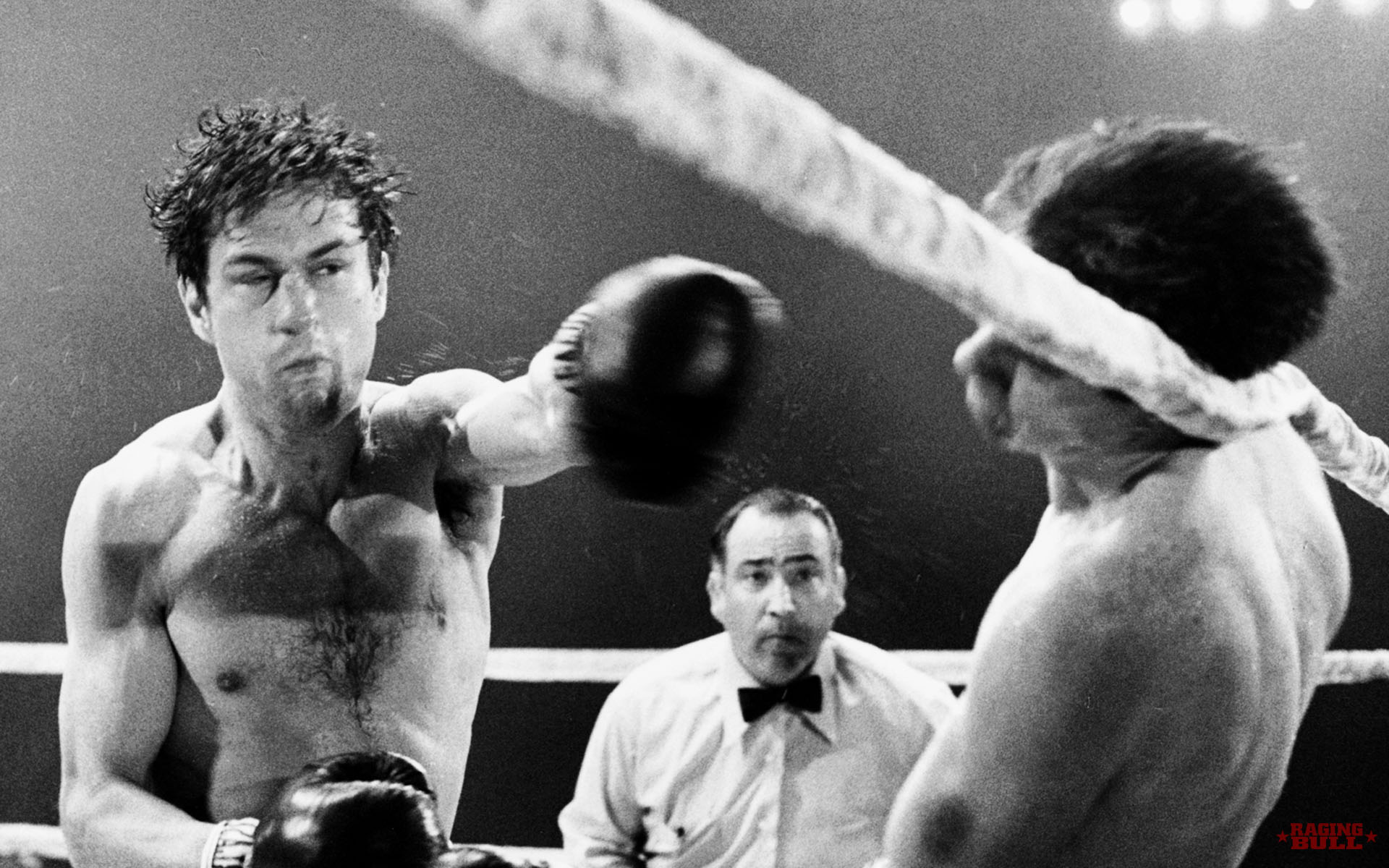

3- Raging Bull (1980)

The greatest sports movie of all time. The (tied) greatest ever De Niro performance (I can never decide between this and Taxi Driver so I’ll call it a tie). The greatest study of self ruination that Scorsese ever accomplished (the two films above this are studies of ruination by other things). Raging Bull‘s one-two punch (sorry) of De Niro and technical wizardry (commonly referred to as the best edited film of all time. In my opinion, that’s probably correct, but Thelma Schoonmaker’s best work is the Sunday, May 11th sequence in Goodfellas. Rant over) cements it as a legendary work. It’s a boxing movie on multiple levels- sure, it deals with Jake LaMotta’s career inside the ring, but it’s also the story of his fight outside of it. And the technical genius of all involved elevate it into a masterpiece (in a way quite similar to the 2009 Claire Denis film White Material, which I will be discussing in a later post. Yeah I’m plugging my own stuff, so what?).

2- Taxi Driver (1976)

A visionary exploration of madness unlike any other. There’s so much going on within Taxi Driver: the film is simultaneously an indictment of the Vietnam war, the vigilante mindset, politics, and child prostitution. And yet it’s an indictment of none of these things. It presents them not positively or negatively, they are. Is Travis Bickle a hero, as he believes himself to be, or is he a violent psychopath? Is he actually lauded for his crimes, or is he imagining this reality as he dies? The film not only refuses to answer these questions, but it doesn’t provide a way to feel about it. It’s a film so important to cinematic history that anything else would feel like piling on. Peter Boyle, who plays “Wizard” in this, is the monster from Young Frankenstein.

1- Goodfellas (1990)

Full disclosure: this is my absolute single favorite film of all time. Nothing else comes close. So it was impossible for me to rank the films of Martin Scorsese with total objectivity. Even so, I have to feel that this would come in first if I could. It’s perfect in every way: Schoonmaker’s aforementioned editing is at its peak, Scorsese’s direction is as good as it’s ever been, the acting all around is brilliant. Liotta, Pesci, Bracco, and Sorvino turn in career bests and De Niro is amazing too. His facial acting in the bar when he decides to whack Morrie is completely incredible. That scene is a microcosm of why the film is so great- it’s the epitome of Scorsese’s cinematic sensibilities. That acting combined with the brilliance of the Sunshine of your Love needle drop and the use of slo-mo is a perfect example of the singular style that propels it into the annals of all time greatness. I could go on listing moments for days- Billy Batts’ death, the tracking shot through the Copacabana, the May 11th sequence, the opening scene, the third wall break, the Layla montage- but the point is already made. The film is perfect, and it’s the summation of Scorsese’s career and the highest peak he’s ever reached. And now we wait for The Irishman.