As I write this, I am watching, for the third time, Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman. It’s one of the man’s greatest films, a gem that unifies decades of thematic fascination into a shattering repression of catharsis. The last time I made a ranking list on this subject, March 26th, Scorsese was a no-doubter for the top position. Now, eight long months later, his spot is legitimately threatened by a challenger who was among the most lauded on the initial iteration. In the time it took to reconsider the 1 spot, the rest of the list underwent dramatic changes, to the point where a rewrite was necessary. So without further ado- the bigger, better, vastly more representative Director Bonanza 2.0.

30- Krzysztof Kieslowski

Last Ranking: N/A

Best Film: Three Colors: Blue

Favorite Film: Blue

Best Moment: In The Double Life of Veronique, when the two Veroniques recognize each other. The ending of Red is up there, though.

Key addition since last list: The final two Three Colors films

Why he’s here: Kieslowski’s Three Colors trilogy is one of the finest of all time, even if the middle segment, White, doesn’t live up to the high bar set by bookends Blue and Red. The Double Life of Veronique further demonstrates the stylistic and thematic brilliance of those films, combining to make a run of singular brilliance from the late master. These are films that hit a specific itch, invoke their own mood, fill a purpose that no other director’s work can.

29- Kelly Reichardt

Last Ranking: N/A

Best Film: Wendy and Lucy

Favorite Film: Wendy and Lucy

Best Moment: If the ending of Wendy and Lucy doesn’t bring you to actual tears, you clearly have no soul.

Key Addition: Old Joy. Nah I’m kidding it’s Wendy and Lucy.

Why she’s here: I once said to someone that Reichardt does Bresson better than Bresson did. This definitely isn’t a one-to-one analogue: for one, Bresson’s brand of minimalism is far more urban than Reichardt’s rural transcendentalism, and you could argue that Bresson’s commitment to non-professional actors is more impressive than Reichardt’s use of, say, Michelle Williams. But while it’s not Bresson’s fault that he didn’t have access to the seemingly limitless talents of Michelle Williams, it is his fault that no performance in his work even enters the same ballpark as Williams in a Reichardt film is capable of. Reichardt sells her visions of American malaise with a naturalistic, almost hypnotic sheen, a style with no real point of comparison, even the jumping-off point I just used. The point remains that Reichardt is an all-time talent- even if what she’s doing really isn’t Bresson (it’s not), she’s operating at a higher level than even that iconic filmmaker ever was.

28- Jean Renoir

Last Ranking: 22

Best Film: Grand Illusion

Favorite Film: Grand Illusion

Best Moment: Grand Illusion‘s prison break

Key Addition: None

Why he’s here: Not only was the early French master a brilliant stylist, he was one of the greatest commentators on the human condition in cinematic history. His films are incisive social statements that, after decades and decades, remain universally relevant in what they have to say about class, race, and how we treat each other in general. The broad tone of Renoir’s work is sad, but not necessarily out of depressing plot mechanics: Renoir gestures at society’s ills and says “what a waste”. It’s really something to watch.

27- Dario Argento

Last Ranking: N/A

Best Film: Suspiria

Favorite Film: Inferno

Best Moment: The doll attack in Deep Red

Key Addition: Suspiria

Why he’s here: Bright colors, gonzo scores, gallons of fake blood. Nobody has ever made a horror movie quite like Dario Argento, the king of the Italian Giallo subgenre. The excess and gleeful insanity of an Argento film are distinctly their own thing, a wonderful combination of elements that collide to create lightning-in-a-bottle phantasmagorias. There’s no way to describe in words the sensory overload of a Goblin score, or the sensation of your eyes under assault by impossibly vivid reds and greens. When this guy was at his peak, his way of doing things was straight-up untouchable.

26- Nicholas Ray

Last Ranking: N/A

Best Film: In A Lonely Place

Favorite Film: It’s Lonely Place, but for the sake of avoiding monotony let’s say They Live By Night

Best Moment: Bogart’s “I was born when she kissed me. I died when she left me. I lived a few weeks while she loved me” from In A Lonely Place. Alternatively, any rodeo scene from The Lusty Men

Key Addition: In A Lonely Place

Why he’s here: Ray’s blend of poison-tongued cynicism and aching romanticism stands alone, in large part due to the fact that nobody from Ray’s era was at his level of pessimism. These are films that really sting, treatises on human despair and why it is that people can never seem to escape it. He was also just a ridiculous stylist, possessing a supernatural gift with both his camera and his actors. In A Lonely Place might be Bogart’s best work, and They Live By Night extracts a haunting performance from the otherwise-shaky Farley Granger. This seems like a common theme so far, but no one has ever made movies like this.

25- David Fincher

Last Ranking: N/A

Best Film: Zodiac

Favorite Film: Gone Girl

Best Moment: Brutal choice, but I think it’s Andrew Garfield’s climactic meltdown in The Social Network

Key Addition: Gone Girl

Why he’s here: A combination of familiarity (a stunning number of my favorite films of recent years) and genuine mastery of the form. Fincher has proven time and time again to be the king of the modern thriller movie- from Seven to Gone Girl, his distinctive style and directorial sensibilities lend themselves perfectly to sheer suspense. The substance of his work is debatable, but the fact that he’s among the best working pure technicians is not. Plus, what other kind of formalist can extract a performance from Ben Affleck as great as what he does in Gone Girl? Points deducted for inane and untrue recent comments on Orson Welles, however.

24- Sam Raimi

Last Ranking: N/A

Best Film: Evil Dead II

Favorite Film: Army of Darkness

Best Moment: “Groovy.”

Key Addition: Army of Darkness

Why he’s here: I think Raimi’s specific brand of genius is best encapsulated by Evil Dead II. No other film is as completely, off-the-walls insane as that one is, for my money. It’s a perfect blend of gleeful gore and pitch-black humor, carried off with the most insane confidence in itself I’ve ever seen committed to film. Raimi’s direction of it can best be described as “swaggering”, the work of someone endlessly happy to be doing what he’s doing and making the exact film he’s making. These are movies that never feel like they’re trying to please anyone besides their creator, and that “who cares” attitude towards anything resembling coherence or subtlety is endearing.

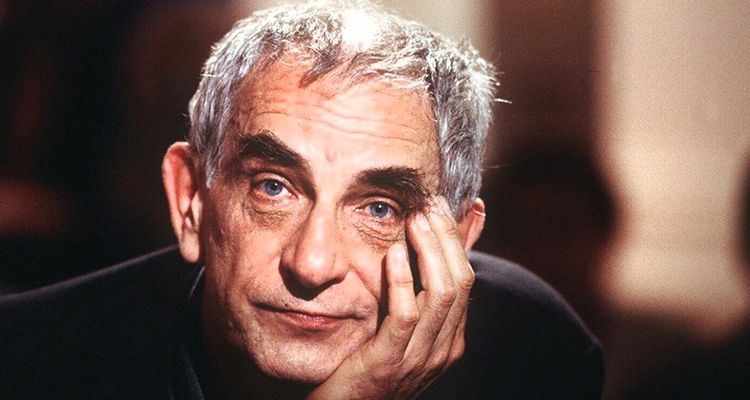

23- Robert Altman

Last Ranking: N/A

Best Film: McCabe and Mrs Miller

Favorite Film: Brewster McCloud

Best Moment: The ending of The Player

Key Addition: All of the above, but especially Brewster McCloud

Why he’s here: Altman is American cinema’s greatest outcast, a startlingly prolific filmmaker who never seemed to land within the mainstream. At his best (see: The Player), Altman’s work was actively malicious towards Hollywood, taking aim at the plastic nature of show business and the despicable self-righteousness of the people who perpetuate it. His work includes anti-westerns (McCabe and Mrs Miller), anti-war-movies (M*A*S*H), and anti-detective noirs (The Long Goodbye). Not only was he doing his own thing, he was aggressively doing his own thing, and he did it well.

22- Stanley Kubrick

Last Ranking: 10

Best Film: The Shining

Favorite Film: The Shining or Eyes Wide Shut

Best Moment: The opening of A Clockwork Orange

Key Addition: The Killing

Why he’s here: You know why. It’s Stanley Kubrick. Inarguably one of the best to ever do it, some would have you believe he’s the best. The work speaks for itself: Dr Strangelove, 2001, Barry Lyndon, Full Metal Jacket, Paths of Glory. Those in addition to the ones I’ve already named. He churned out masterpieces with an absurd success rate, delivered many of the most iconic films and moments of all time. Plus, Eyes Wide Shut is the greatest Christmas movie ever made.

21- Hayao Miyazaki

Last Ranking: 19

Best Film: Spirited Away

Favorite Film: Kiki’s Delivery Service

Best Moment: The climactic battle in Princess Mononoke

Key Addition: Porco Rosso

Why he’s here: Possibly the only person to fully understand the true boundaries (or lack thereof) of the medium of animation. Combine his wondrous visual style with his unique and heartwarming humanism, and you have a set of films that stands as nothing less than an example of the good in the word. This is the mind that created a dazzling army of magical creatures that he routinely uses as window dressing for larger work– it’s unnecessary stuff, but it’s there nonetheless. Miyazaki’s films are his attempts at improving the world through art, and he more or less succeeds.

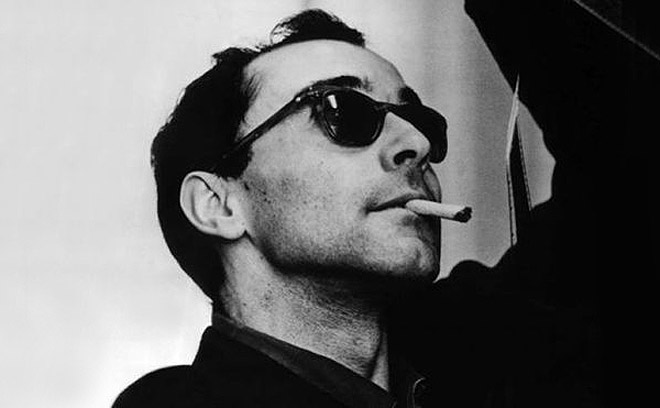

20- Jean-Luc Godard

Last Ranking: 12

Best Film: Pierrot Le Fou

Favorite Film: Pierrot Le Fou

Best Moment: Vivre Sa Vie, pool hall

Key Addition: Une Femme est Une Femme

Why he’s here: The best of all the French New Wave filmmakers, Godard has been described as an iconoclast so many times that it’s formed the basis of his iconic status. His work has a disorienting yet breezy style, almost nihilistic yet simultaneously drunk on life. He sought to elevate B-Movie sleaze into legitimate art and pulled it off, inspiring a generation of other filmmakers in the process (you may have heard of Quentin Tarantino).

19- David Cronenberg

Last Ranking: 17

Best Film: The Fly

Favorite Film: Eastern Promises

Best Moment: William Hurt, A History of Violence: “HOW DO YOU FUCK THAT UP?”

Key Addition: Dead Ringers

Why he’s here: Cronenberg’s fascinations with evil, with humanity, and with how those two things complement each other fascinates me. The way he explores these fascinations, through a ridiculously bloody brand of body horror, has made him infamous. Not only does Cronenberg pile on the gore, he does so in a way designed to upset the viewer at a gut level and to make them think about what they’re seeing in the same place. The truths of interior human evil, revealed. With exploding heads!

18- Claire Denis

Last Ranking: 15

Best Film: Beau Travail

Favorite Film: US Go Home

Best Moment: Beau Travail, “Rhythm of the Night”

Key Addition: None

Why she’s here: Denis creates films that slow to a stop, forcing you to contemplate what’s in front of your eyes. Fortunately, what that is is beautiful– Beau Travail in particular has some of the most mesmerizing cinematography I’ve ever seen. Unfortunately, it can also get real hard to watch (see: all of High Life). Regardless, Denis makes films that are guaranteed to stick with you, portraits of cosmic loneliness in which movement and lack thereof are the most important things. This is visual and aural hypnosis, a perfect use of everything the medium is capable of.

17- Joel and Ethan Coen

Last Ranking: 11

Best Film: No Country For Old Men

Favorite Film: The Big Lebowski

Best Moment: Ben Gazzara as Jackie Treehorn

Key addition: My most recent rewatch of No Country

Why they’re here: The batting average. Ignoring, for a minute, the level of quality of their top tier of films, it’s so rare to find anybody this prolific with this few misses. That’s especially impressive considering the uniform nature that should envelop their work, which is instead shockingly eclectic. They use the same actors, same technical contributors, write the same way, explore the same ground, over and over again. Yet the gulf between the desolate deathdream of No Country for Old Men and the spirited frenzy of Raising Arizona is massive. Look at two of their stories of tortured, hopelessly constricted, neurotic individuals: A Serious Man is an absurdist comedy while Barton Fink is a post-gothic thriller. And, most importantly, it’s all good as hell.

16- Ingmar Bergman

Last Ranking: 13

Best Film: Persona

Favorite Film: Wild Strawberries

Best Moment: Chess with death! Gotta be chess with death

Key Addition: Hour of the Wolf

Why he’s here: Patron saint of art films, cinematic austerity, and everyone who has ever refused to watch a foreign movie out of preconceived notions of guys dressed as death talking about God. It’s a justified reputation to some extent, but where Bergman soars is in the violations of this. The Seventh Seal, as many have pointed out, has fart jokes in it. Some of the stuff in Hour of the Wolf will give you nightmares. The Magician gets weird, man. But he’s also masterful in the stereotyped ways, and there’s nothing wrong with that– sometimes pitch-perfect arthouse stuff just hits the spot.

15- Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

Last Ranking: 24

Best Film: The Red Shoes

Favorite Film: The Red Shoes

Best Moment: Marius Goring complimenting the technicolor in A Matter of Life and Death

Key Addition: A Matter of Life and Death

Why they’re here: Because of cinematographer Jack Cardiff, actually. Well, maybe not actually. But he played a big role. The key element of an Archers film is the look, the picturesque fairytale technicolor that serves as the backdrop for whatever rapturously told story they’ve zeroed in on. From here, they routinely go on to spin magic, creating some of the most indelible moments in cinematic history. Also, The Red Shoes is just the best movie there is.

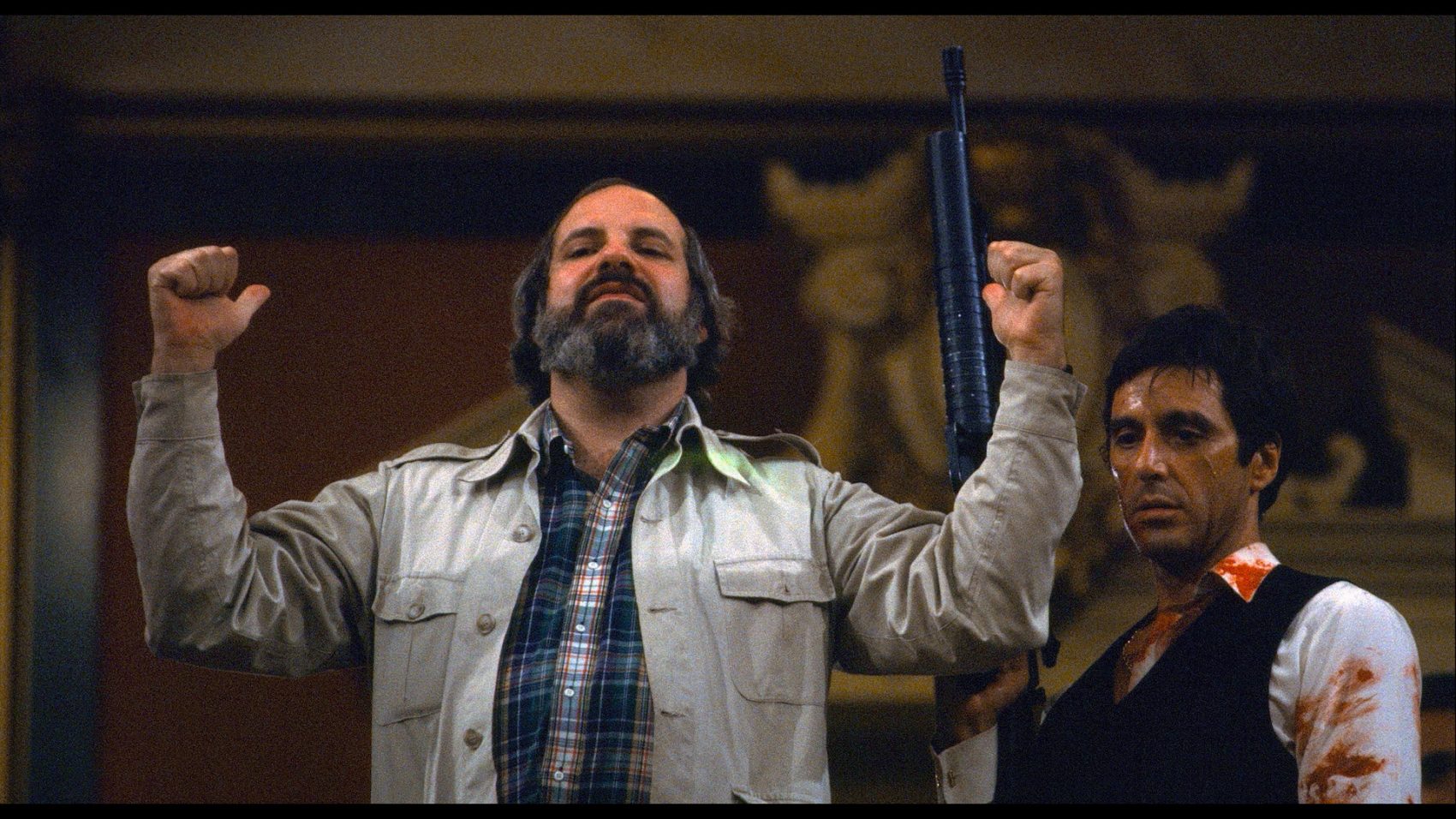

14- Brian De Palma

Last Ranking: 23

Best Film: Blow Out

Favorite Film: Phantom of the Paradise

Best Moment: “Now that’s a scream.”

Key Addition: Phantom of the Paradise

Why he’s here: His at-large career of lurid trashterpieces is enough to merit inclusion: Scarface, Blow Out, The Untouchables, even, all brilliant thrillers and crime films from the master of the post-Hitchcock thriller (emphasis on “Hitchcock”). But De Palma’s greatest asset in my mind is the cult classic 1974 musical Phantom of the Paradise. Upstaged a year later by another rock-and-roll fantasy horror cult musical freakout by the name of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, a film it is better than, Phantom instantly joined the annals of my absolute favorite films upon my first viewing. That film might have the biggest single impact of anything on this list, skyrocketing De Palma from the 20s to the lower teens.

13- Pedro Almodovar

Last Ranking: 5

Best Film: Talk To Her

Favorite Film: Pain and Glory

Best Moment: Last time I said the mirrored beginning and ending of Talk To Her, which is a strong call, but I think I’m leaning more towards the drugged-out post-screening Q&A in Pain and Glory

Key Addition: None

Why he’s here: “Melodrama” is a word that’s often (accurately) applied to the work of Pedro Almodovar, but I don’t think I find that quite fitting. The exteriors of his films are often showy, playing into the conventions of the term, but he also imbues them with an uncharacteristic tinge of sadness. What separates Almodovar from, say, Douglas Sirk (possibly the last name cut from this list, by the way) is the way he contrasts his searing insights with grinning exuberance. Never has sadness been as life-affirming as it is in these films.

12- Yasujiro Ozu

Last Ranking; N/A

Best Film: Tokyo Story

Favorite Film: Tokyo Story

Best Moment: Ending of Late Spring

Key Addition: Tokyo Story

Why he’s here: It’s kind of hard to describe, actually– what Ozu does with his films is so simple that it feels odd to label him a visionary, yet so idiosyncratic that some of those unfamiliar and familiar with his work alike question its efficacy. This could be the part where I go over the Patented Ozu Aesthetic, with its static cameras, facing-the-viewer dialogue, and establishing “pillow shots”, but as people smarter than myself have pointed out, overly scrutinizing these tics is to miss the point. What Ozu builds with his formally dressed narratives is nothing short of full-on emotional oblivion. This is evocative work– whether it’s driving at sadness, empathy, or introspection, an Ozu film can elicit this from its viewer. He manages to build to final acts of stunning focus and intensity, rendering his films completely indelible. And he does it in style: just because the item at the forefront of discussion of Ozu shouldn’t be his mechanics doesn’t mean I don’t want to take a second to absolutely fawn over him as a technician. I feel like I’ve said this a hundred times so far, and it remains hard to fully communicate the sentiment without just showing one of the films I’m talking about, but genuinely nobody has ever made movies like this, and I am obsessed with it. He was totally singular in his construction, and his astounding humanist storytelling is all the more alluring because of it.

11- John Cassavetes

Last Ranking: N/A

Best Film: Husbands

Favorite Film: The Killing of a Chinese Bookie

Best Moment: The scene with the parents in Minnie and Moskowitz

Key Addition: Husbands

Why he’s here: For oddly similar reasons to Ozu, actually– the simultaneous devastation and humanism of Cassavetes’s work is incredible to watch in much the same way. Now, this comparison makes it sound like I’ve never seen anything from either filmmaker; the two couldn’t really be more stylistically different, with Cassavetes opting for brutal, unflinching realism opposite Ozu’s stylized elegies. Cassavetes allowed himself to get much more raw than other filmmakers, a quality that resulted in some of the most deeply penetrating work of his era. His films can get hard to watch, in a way that makes them hard to take in in quick succession. But they’re incredible: searing, haunting stuff, at times feeling like he’s probing the adequacy of humans as a species. But it’s the optimism of his work that really gets me. Sure, these are bleak, depressing films, but there’s always a hard-to-pin-down undercurrent of genuine hope for and faith in human beings.

10- Bong Joon-Ho

Last Ranking: 21

Best Film: Parasite

Favorite Film: Parasite

Best Moment: Parasite‘s multitude of gargantuan setpieces have been repeatedly spoken for on this blog, so I’m gonna give a shoutout to the first monster attack scene in The Host, a scene so surreal yet poignant that it achieved the rare accomplishment of actually making me put myself in a horror scene: it feels like it’s absolutely something that could happen to you, and that’s uniquely terrifying.

Key Addition: Memories of Murder

Why he’s here: Surely the Cinderella Oscar darling and subsequent international sensation that is Bong Joon-Ho doesn’t need much of an introduction here, right? The proper content in this space is an affirmation that he really is deserving of all that, and uniformly so: Parasite may be his finest moment, but the likes of Memories of Murder, The Host, hell, even Okja are all masterpieces. The man routinely hits this blend of pure entertainment and dramatic resonance that’s totally unparalleled. It makes sense that Bong was really the biggest modern international filmmaker to break out in America. Who else makes movies that are this self-evidently great in this number of ways?

9- Orson Welles

Last Ranking: N/A

Best Film: Screw it. It’s The Lady From Shanghai

Favorite Film: Lady From Shanghai. Sometimes I wonder about the extent to which this category is worth keeping.

Best Moment: How about the opening tracking shot in Touch of Evil? Also a big fan of his concluding revelation of his true nature in F For Fake. Obligatory Kane mention for the scene where he finishes a negative review of his wife’s opera performance. Too much great stuff.

Key Addition: Lady From Shanghai

Why he’s here: If you subscribe to the conventional narrative, brought back into the spotlight by David Fincher’s latest effort, that Welles was a one-hit wonder who fell off after his momentous debut, then it’s my great pleasure to inform you that you’ve been fed a horrendous lie. Welles’ post-Citizen Kane career was fraught with studio interference and a lack of commercial success, sure, but what never dropped off was the absurdly high quality of his work. This was a man gifted with absolutely astonishing talent both in front of and behind the camera, who was somehow successfully painted by Hollywood as an obnoxious prodigy who flew too close to the sun. The work, however, speaks for itself, and it’s hard to argue with.

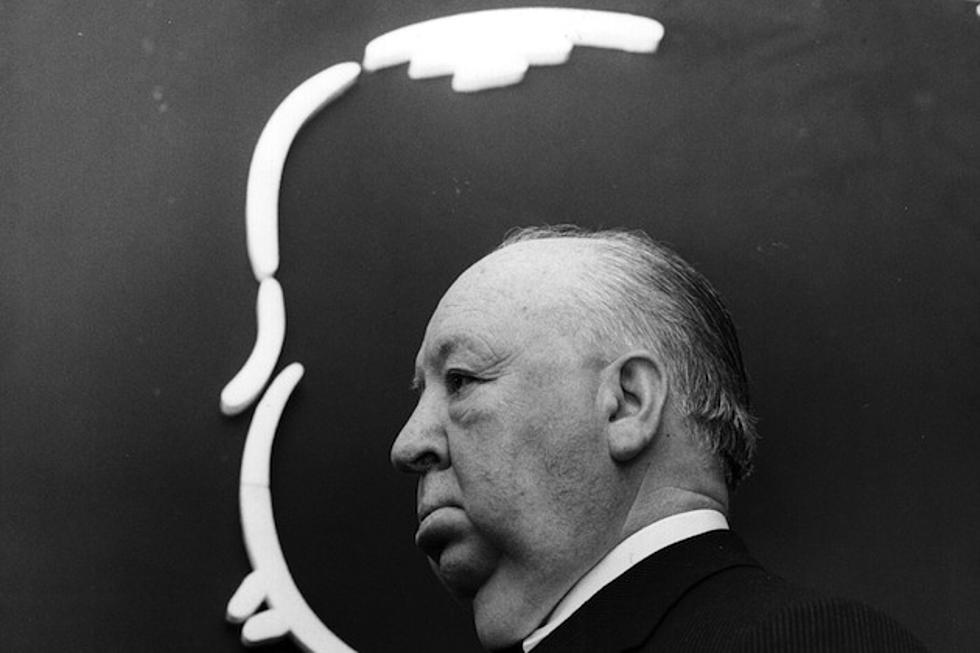

8- Alfred Hitchcock

Last Ranking: 4

Best Film: Vertigo

Favorite Film: Psycho

Best Moment: Too many iconic ones to not go with something completely random. How about, like, the scene in I Confess where they’re chasing a murder suspect and need a confirmation or denial from Montgomery Clift, who has to remain silent? That’s the stuff.

Key Addition: Rebecca

Why he’s here: Because of the consistency with which his movies are fun. Lesser or unknown Hitchcock can compel reverence and titillation in the face of any amount of fatigue, ubiquity, or oversaturation. It feels like a cop-out to say something along the lines of “it’s Alfred Hitchcock”, but come on. It’s Alfred Hitchcock. Not overrated, not remotely mundane. Just too good.

Bonus, unranked- Stan Brakhage

Why he’s here: This has to be both an explanation of why he’s here, as in on the list, and why he’s here, as in sandwiched unceremoniously as an honorable mention between the numbers eight and seven. The answer to the latter is simply that this is where it hit me that I should include him, and for the sake of cohesiveness I decided to just put him in chronologically. Brakhage demanded inclusion because he is, undeniably, one of my favorite filmmakers, but it’s also pretty much impossible to rank him among narrative filmmakers. It’s not exactly apples to oranges so much as it’s apples to moons of Jupiter. The typical superlatives have been eschewed because, uhh… well if you know, you know. It’s hard to describe Brakhage’s work, and it’s impossible to describe why I find it to be so good without sounding like a complete lunatic. Basically, for those uninitiated, Brakhage was an experimental filmmaker who specialized in what I have routinely referred to as nonsense color blobs. That is, I’m sure you will agree, an apt description–

Not all of them are quite as short as Eye Myth here, but that’s the general gist. Yet there’s something about these films that are so hypnotic, so compelling. Maybe it’s the illusion of movement you get in different places, maybe it’s the assortment of the colors. I don’t know why it is that some of his work stands out from the rest, or how much sense it makes to differentiate between them. But I do know that, for whatever reason, this stuff can be really, really good.

As I write this, my viewing of The Irishman that kicked off this post has been over for a month. I’ve revisited this from time to time to chip away at the writeups, getting up to this point, but I’m confronted by challenges. I’m miles from any sort of momentum or tone I was trying to build with the prior writing. I’m freaking out because I think I need to find a place for Michael Mann following viewings of Thief and Manhunter (this cursory reference will do, I guess). Inertia? Burnout? Yeah, all that– at some point it gets to a place where I’m writing different forms of the same auteurist set of ideas and praises.

So, to break up that monotony and to slide back into this post, I’m going to do something completely different: I’m going to take a minute to talk to you about The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2.

It is rare, in the wide, godforsaken world of horror sequels, to run across a beast in a similar vein as Texas Chainsaw 2. The lunatic depravity of the first film is spun here into pitch-black humor and nightmares as bizarrely outlandish as the reality of those in the original. Instead of chilling, cheap realism, we’re treated to a chainsaw-wielding Dennis Hopper losing his mind. The first film’s Leatherface, a mindless, thoughtless creature of pure murderous intent, is transformed into something almost akin to a child– bloodthirsty, yes, sadistic, still, but imbued with almost… innocence? A sense of curiosity that maybe his life of cannibalism isn’t all there is. The film’s greatest trick is burying a tragic humanity within its gonzo carnival exterior. The choice poised by the Sawyer patriarch to a simpering leatherface, “sex or the saw”, is, of course, absolutely hilarious. But digging into it, it’s also heartbreaking: this is a person forced into a life of torture and murder and horror beyond comprehension as if it was just another family business. Any real life, real human emotion or experience, that could have possibly awaited him was instead demonized and presented as something foreign and terrifying. Texas Chainsaw 2 gets into what it really means to live by the saw, something far more impressive than you’d expect from a tossed-off sequel to an incomparable classic.

Why does this matter? To the theme of this post, to anything, really? It doesn’t. Anyway, on with the show.

7- Quentin Tarantino

Last Ranking: 3

Best Film: Pulp Fiction

Favorite Film: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

Best Moment: Zero options that aren’t the climactic theater burning in Inglourious Basterds, perhaps the greatest single scene in the past two decades of American film

Key Addition: N/A

Why he’s here: The one-two punch of brilliant dialogue (not diminished by countless inferior imitators) and brilliant building of tension is unmatched by any other mainstream filmmaker of the modern era. Anyone with the industry cache to make a hangout movie at the scale of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a force for good, even if his unleashing of Robert Rodriguez onto the world is a negative.

6- David Lynch

Last Ranking: 8

Best Film: Mulholland Drive

Favorite Film: Eraserhead

Best Moment: In a filmography packed with indelible moments, it’s hard to pick one, but I’ll give a shoutout to the one that’s been bouncing around my head the most recently, which is Dean Stockwell’s Roy Orbison lipsyncing in Blue Velvet.

Key Addition: The entire Twin Peaks universe: the original run of the show, the unfairly maligned Fire Walk With Me, and the stunning The Return (I choose not to comment as to whether this is a movie or TV)

Why he’s here: the glorious weirdness coursing through Lynch’s work has long been tagged “Lynchian” and gleefully, erroneously identified as anything in film that borders on the supernatural, but there’s a very specific set of themes, motifs, and out-of-this-world ideas that populate the man’s oeuvre. The style makes for fantastic viewing experiences: I’ve seen Eraserhead four times now, a feat of blatant masochism made compelling only because of how much of a perverse joy the film is. But the key to Lynch, the piece of the puzzle that the endless pretenders to his gnarled throne can never find, is the way his films sink into the mind of the viewer and settle there for a long time. Sure, the ending of Twin Peaks: The Return is nonsense, but it’s nonsense that will be with me for the rest of my life.

5- Paul Thomas Anderson

Last Ranking: 7

Best Film: There Will Be Blood

Favorite Film: Boogie Nights

Best Moment: The New Year’s’ Eve scene in Boogie Nights

Key Addition: Magnolia

Why he’s here: 25 years, 8 films, 0 misses. Each PTA film is uniquely stunning, forming a progression of ideas and techniques that indicates the work of a remarkable natural talent the likes of which we haven’t seen in Hollywood since Welles. The balance of singular cinematic prowess and raw emotionality present in everything he’s made since Boogie Nights makes him one of our most incredible working filmmakers, someone whose work lends itself to endless rewatches and whose next step is eagerly awaited.

4- Akira Kurosawa

Last Ranking: 9

Best film, favorite film, key addition, greatest movie ever made: Ran

Best Moment: The castle battle sequence (behind the scenes of which shown above) in Ran

Why he’s here: Every time I find myself mulling over the question of who the greatest filmmaker of all time is, I tend to land on Kurosawa. Sometimes I’ll falter, and entertain the idea of an Ozu or a Hitchcock or a Scorsese taking the spot. And then whenever the next time I watch a Kurosawa film is, I get my mind back on the right track and recognize the folly of my fleeting opinion. The man was simply the best there ever was: so energetic in his storytelling, so vivid in his imagery, so human in his characterizations. Whether it’s the adrenaline of samurai-action fare such as Seven Samurai, the heartbreaking sincerity of Ikiru, the epic grandeur of Ran, or the electric crime thriller elements of something like High and Low, there’s always something to marvel at in his films. Take High and Low, a taut crime procedural propelled by a life-and-death storyline. When I say that every single shot in the film is composed with an immaculate sense of positioning, I mean all of them. Every time someone moves or a group of people congregate, they’re arranged in a visually striking way that compels awed reverence that almost distracts from the story at hand. Or Ran, Kurosawa’s take on Shakespeare’s King Lear, a film I believe with full conviction to be the greatest ever made. Not only does this trim a lot of the Edgar/Edmund fat that populates the play, it manages to translate the visceral pain and sorrow of the source material that makes it one of the greatest works of literature ever produced. Not only does the beating heart of the play remain stunningly intact in a way seen in no other Shakespeare adaptation, the visuals of the film are simply breathtaking, managing to elevate it into something wholly its own. I could go film-by-film and break down everything that makes Kurosawa’s work so varied and special, but it would take far too long. So suffice it to say that this is a body of work that represents a complete cinema. Everything in film that makes the medium so dynamic and wonderful can be found in these movies.

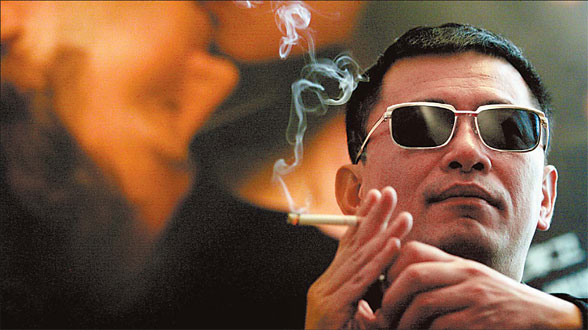

3- Wong Kar-Wai

Last Ranking: 6

Best Film: In the Mood for Love

Favorite Film: Chungking Express

Best Moment: The ending of Fallen Angels: the motorcycle shot, the voiceover, all beautiful, and then the pan up to natural sunlight, punctuating a film bathed in artifice and neon? Gets me every time.

Key Addition: 2046

Why he’s here: Nobody’s individual style is better than Wong’s. All the hallmarks of his work– the slo-mo, the alluringly unnatural lighting, the voiceovers, the music use– gel together to create a series of films that resonate with a feeling that’s impossible to put into words. I’m convinced that there is no one who has ever lived who’s been as understanding of the human soul as Wong Kar-Wai, which is what gives his films their heart. Which is an added bonus: let’s be real here, the real draw of a Wong film is how cool they all look. Even with no subtitles or any understanding of the language spoken, these films are still probably something else to watch. And they’re so in line visually with Wong’s fascinations that they still probably communicate the same tones of loneliness and oddly comforting ennui.

2- Martin Scorsese

Last Ranking: 1

Best Film: Goodfellas

Favorite Film: Goodfellas

Best Moment: Leonardo DiCaprio’s drugged-out dash home in The Wolf of Wall Street is the freshest in my mind, so I’ll go with that

Key Addition: The Age of Innocence

Why he’s here: with the prior unquestionable #1 on this list, this section feels like it should read as a condemnation, an explanation of a fall from grace. In reality, there’s been no lessening of my opinion of Scorsese: I still view him as a titanic cinematic figure, a brilliant craftsman and a straight-up saintly presence in the world of film preservation. He’s a crusader in the fight to save the soul of cinema from the encroachment of the monotonous blockbuster. A voice for the distribution and promotion of films from countries with less-than-established film industries. And he’s one of our best working filmmakers in his own right: for anyone who thinks he only makes gangster movies, I’d advise checking out Age of Innocence, that thing is astonishing.

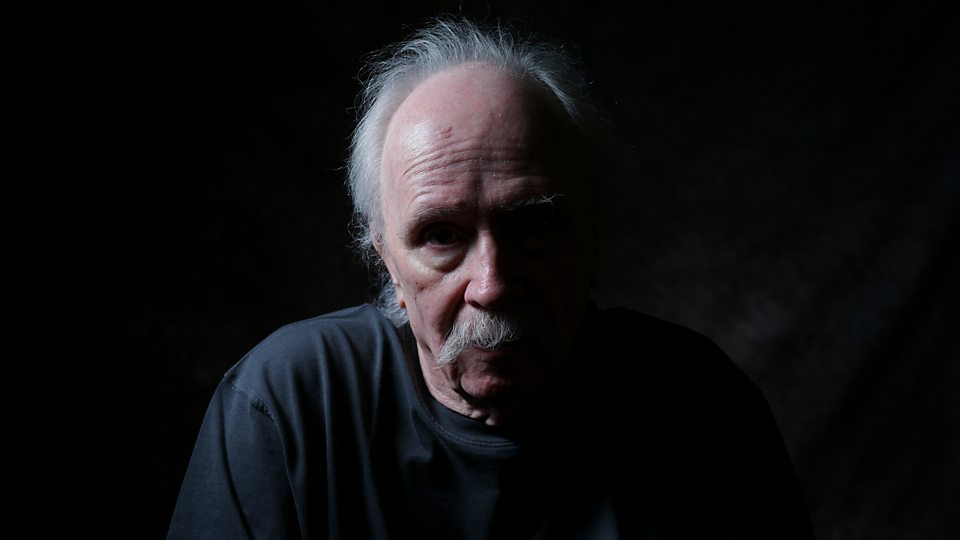

1- John Carpenter

Last Ranking: 2

Best Film: Halloween

Favorite Film: Big Trouble in Little China

Best Moment: Hmm. Let’s call it the scene in Prince of Darkness where the guy explodes into bugs while telling everyone else to “pray for death”. I like that one.

Key Addition: Honestly, the key thing in the last few months with Carpenter was rewatching most of his films, sometimes repeatedly. But I also did see Escape From L.A., which I think cemented for me the idea that even when one of his films isn’t, how you say, “good”, it’s still astonishingly entertaining (this is not true of the bland Village of the Damned, which isn’t really bad so much as it is uninteresting: you can feel his lack of enjoyment with the project). Oh and Body Bags, Body Bags completely rips.

Why he’s here: Rewatch value? Enjoyability? There’s a quality to his films that extracts from me a total obsession, but I’m not sure it’s anything that simple. There are a solid dozen Carpenter flicks I can put on at any moment and have an absolute blast with. There are a handful that I count among my favorite films. There’s one (Big Trouble in Little China) that probably stands as my favorite movie of all time. His more outright horror movies are seasonal necessities for me (getting through October feels incomplete without the uniquely chilling atmosphere of Halloween). The best example of his brilliance is honestly evident in something like Christine: an adaptation of a C-list Stephen King novel with a story revolving around a murderous car. It shouldn’t work, yet it manages a narrative brilliance and emotional core that elevates it into a masterpiece. His gifts in the more traditional realm are outweighed by his ability to create absolutely demented atmospheres and images. I’ve discussed Halloween, but that excludes the lightning-in-a-bottle ghost story The Fog, the oppressive paranoia of The Thing, the Lovecraftian nightmares of In the Mouth of Madness. I still have yet to namecheck They Live, a careening, disillusioned, outstanding political allegory about a group of capitalist aliens who have taken over the world, and Assault on Precinct 13, a gritty zombie movie that happens to not feature or mention any zombies. I love all of these. These are films embodying cinema as a propulsive force. Life not so much refracted through a fantastical lens, but reformed and reshaped in a recognizable but alien depiction of our world as a magical, terrifying alternate reality.

There is no way to end this but to play it out with the worst song in recorded history:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/63209648/US_1.0.jpg)