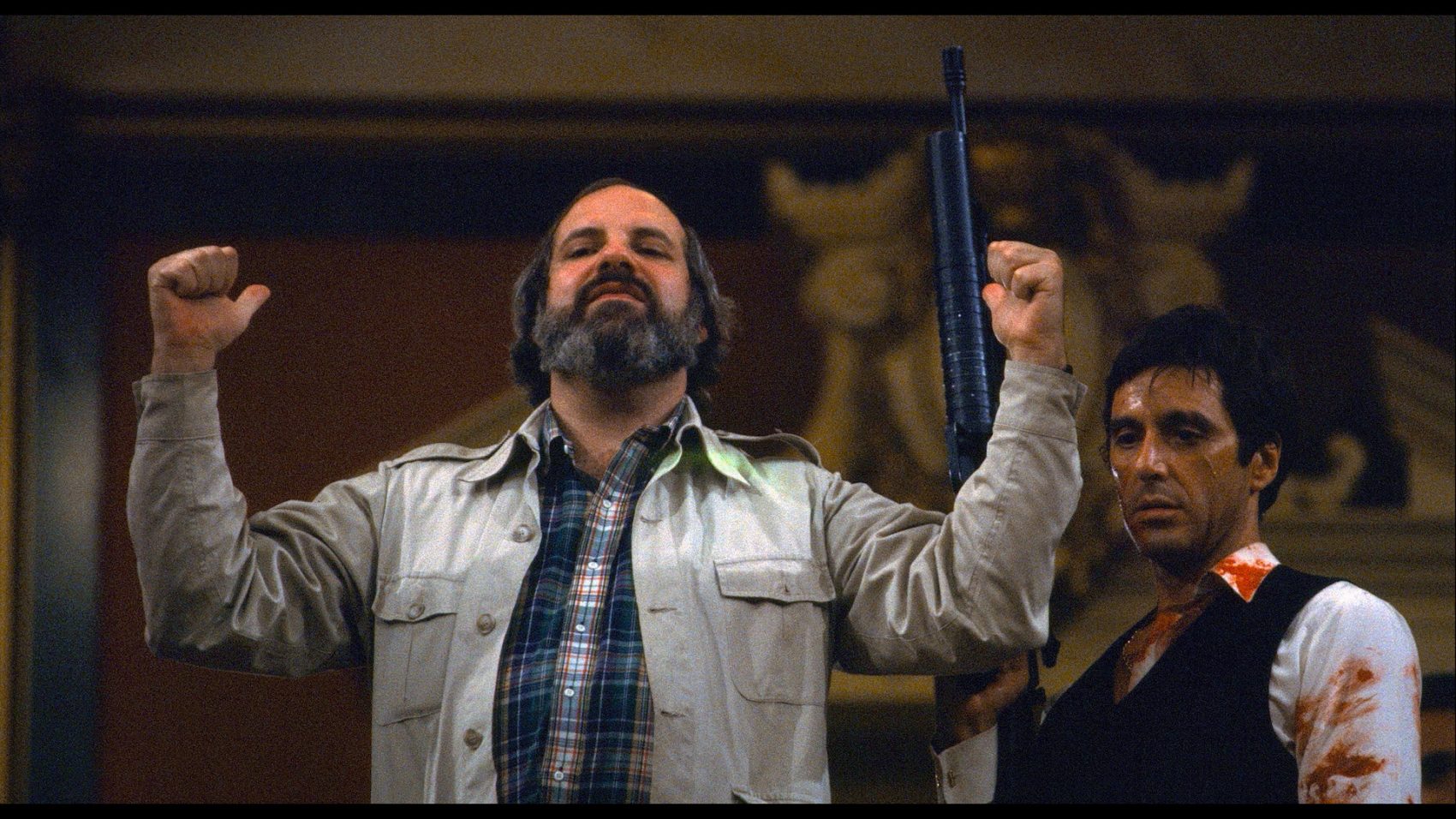

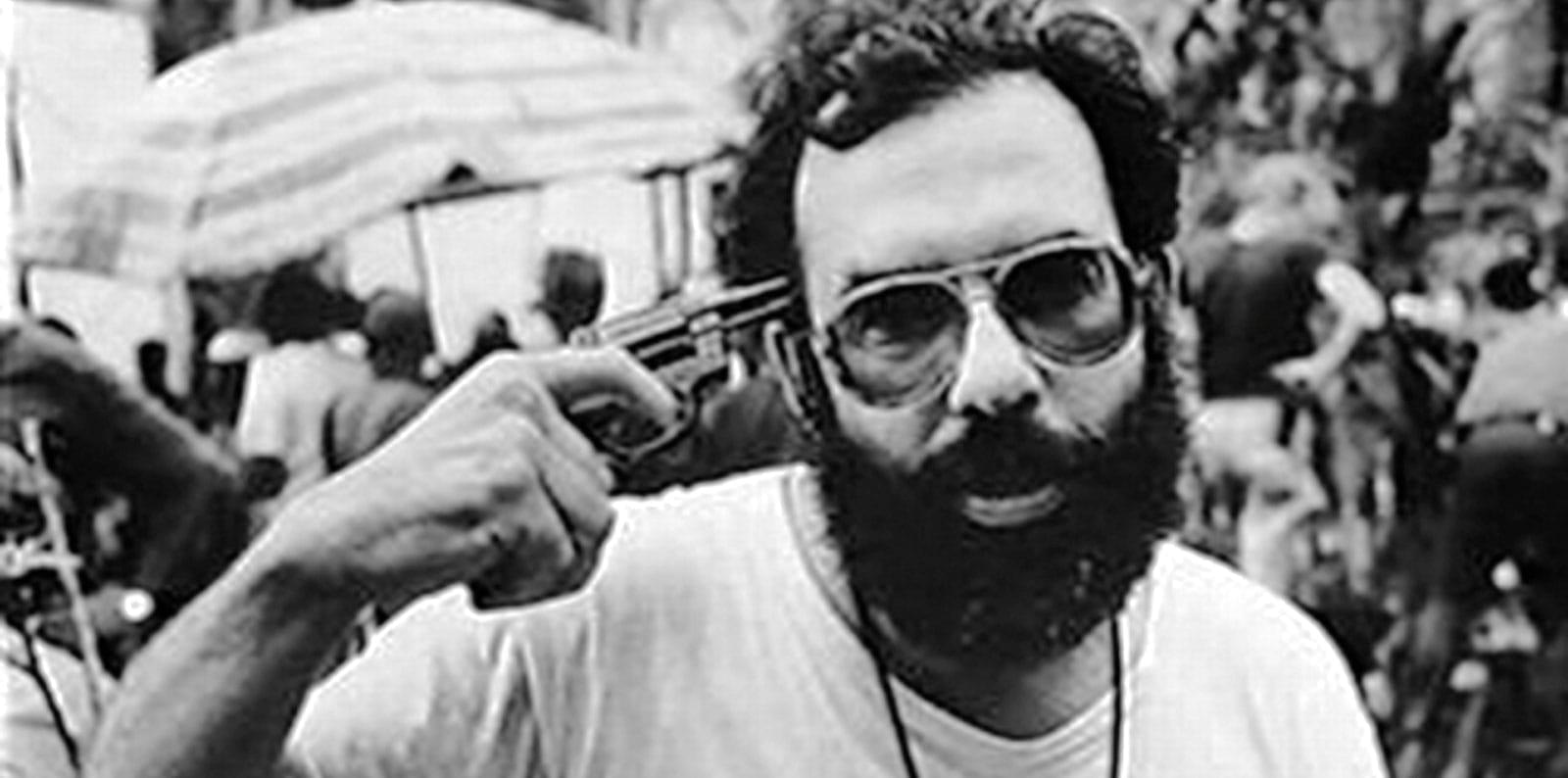

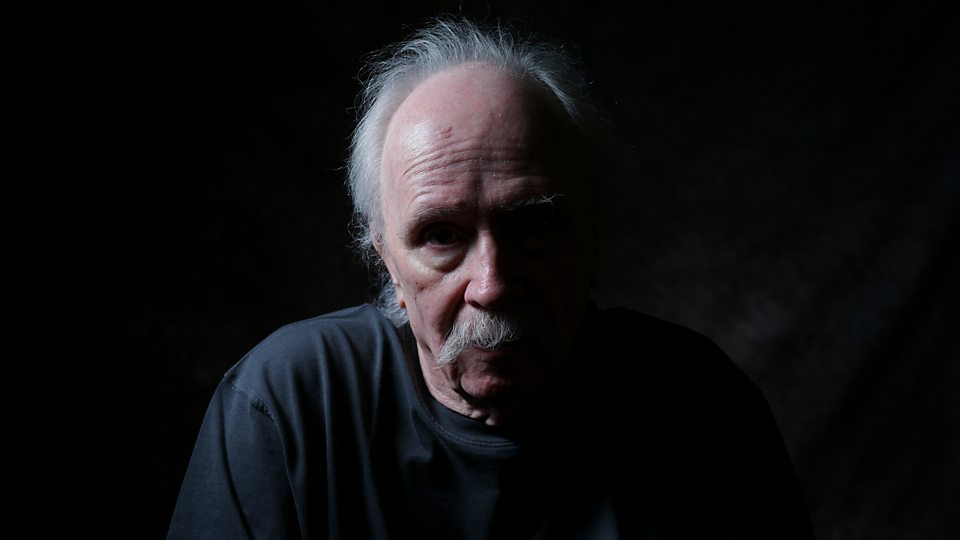

Just shy of 40 years ago, in February of 1983, Canadian horror filmmaker David Cronenberg received studio money to unleash Videodrome, a gruesome paranoid thriller about a sleazy TV executive who stumbles upon a channel airing, seemingly, snuff films. Smuggled into the film behind the likes of James Woods and Blondie frontwoman Debbie Harry were piles of Cronenberg’s trademark gore, viscera, and fascinations with transformations of the human body. He lost that studio money. Cronenberg was, by a month, still in his 30s at the release of Videodrome. He was young, spry, full of ideas. The poor box-office reception of that film wouldn’t slow him down, as for the foreseeable future he went further into his controversial, often unappealing idiom.

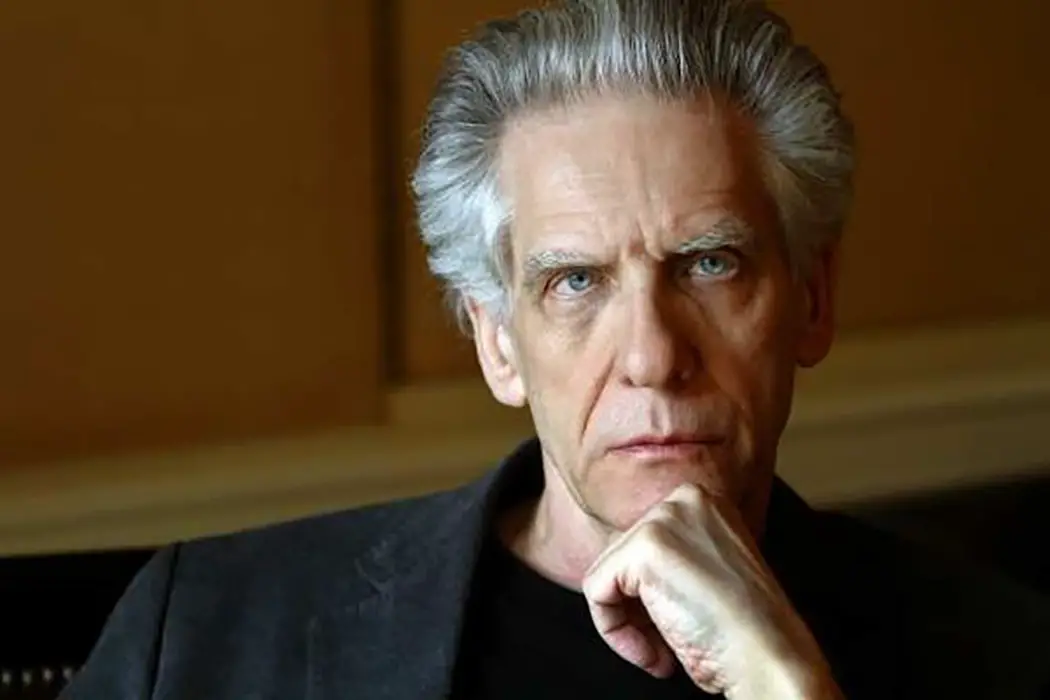

Today, David Cronenberg is 79. Eight years have passed since Maps to the Stars, until recently his latest film, debuted at the Cannes film festival. In those eight years, the popular wisdom seemed to become that he had entered a state of semi-retirement. No projects were announced, no indication of movement. In the 21st century, it was starting to look like he had outgrown his trademark body horror, moving towards more contemplative and dramatic examinations of his fascinations such as A History of Violence and Eastern Promises. The violence and tone remained, the running threads about blood, transformation, what it means to be human, all survived, all existed as an unmistakably distinct marker of the man’s work. But the man himself, in step with his career-long question about how much we can change before we are no longer ourselves, had encountered a fundamental shift. And then he stopped. It felt natural, in a sense. Maybe he had said all he had to say.

In 1970, Cronenberg directed Crimes of the Future. This was even before the early period when he first clicked with the body horror that would become his MO, putting out films like Shivers and The Brood. This was Cronenberg in his infancy. Crimes ran about an hour long, and its reputation in today’s Cronenberg canon is that of an oddity, even a failure, a diehards-only affair that really isn’t all that significant but for being prehistoric. It earns this, never seeming fully assured of its themes or why its visuals are the way they are. In the film, you can see Cronenberg forming, but it is unclear what he’s working towards. Something was missing.

In early 2021, Viggo Mortensen revealed that Cronenberg had something else cooking. It was to be his first body horror movie since 1999’s eXistenZ, his triumphant return to the genre with which his name was always fated to be intertwined. He was finally filming a script he had been kicking around for decades, since he was a younger man. Only in his late 70s was he ready to bring it to the screen. When originally conceived, Cronenberg had given it the name Painkillers, but for its long-awaited entry into reality, he decided upon another title: Crimes of the Future.

This marked the beginning of the end of a series of long processes for Cronenberg: returning for his first feature film since 2014, returning to body horror for the first time since 1999, returning to the script for the first time since its abandonment in the early 2000s, and returning to that title, vividly evocative but lost on a film nobody remembers, for the first time since 1970. In the eyes of the public, it was the beginning of a cycle leading to the film’s release. But, fittingly for a film about, among other things, the agony of artistic creation, the weight of the factors that had gone into its arrival meant that the remaining cycle was merely the tip of the iceberg.

So, in the end, what’s the film we got out of all this? In short, it’s a masterpiece, a vintage example of Cronenberg’s fixations and stylistic tics. But it’s also completely befitting of what led to it. As mentioned, the new Crimes of the Future focuses on artistic creation, legitimizing the term “suffering for your art” in new ways: the main character, Saul Tenser (Mortensen), is a performance artist of great renown whose performances consist of the surgical removal of internal organs. These organs are entirely new, heretofore unheard of ones that Tenser grows spontaneously. In this process, Cronenberg zeroes in on the subject of bodily transformation that he has confronted in his art for decades, but reaches a new, self-referential question: are these transformations, in and of themselves, art? It’s a question Saul Tenser seems wary of, despite his own role in perpetuating the idea that it is. His art seems to inspire people to reach a variety of different conclusions: government agent Timlin (Kristen Stewart) defends it at one point by saying “many people respond to it”, an idea that she exemplifies perfectly. The art speaks to her in a way that consumes her, rewires her personally. For others, it sparks a political drive, emblematic of the idea that these growths are beautiful. An underground network of radicals who believe in eating plastic and embracing evolution others see as dangerous views it as perfectly designed to deliver a message. For Tenser, at least at the film’s onset, the art simply seems to be in the act of removal, and even this is unsure to him. His partner, Caprice (Lea Seydoux), views this removal as both artistically resonant and functionally necessary. All of these interpretations, often confusing and overlapping, spring from an act that is, by its artists, viewed as something akin to removing tumors.

The obvious way to view Tenser, and almost certainly the correct one, is as an analogue for Cronenberg. In his decades-long career, he has prodded at visceral, ugly obsessions on screen to an incredibly wide range of reactions: disgust and admiration, derision and acclaim, designation as both a peddler of shlock and an essential artist. The forces pressing down on Tenser are so disparate that his indulgences of them are easy to take as cool ambivalence, furthering a portrait of Cronenberg himself as an artist lost in perception of his art. The political movement that seeks to recruit Tenser into their cause views his art as a rallying cry celebrating the inner beauty of the human body; Tenser points out that his art centers on the removal of that beauty, inherently uninterested in letting it exist inwardly, yet the idea stays with him. The government agent who serves as Tenser’s contact in his capacity as an informant doesn’t see the point in his performances. Neither, to some extent, does Tenser; they’re useful as a job, or as a cover for his work with the government. Yet he feels compelled to defend his art, maybe buying into his own myth, maybe truly connecting with it. As his body changes, the changes themselves start to change. Tenser understands these fundamental movements, and has made himself amenable to them, liquid. Nothing is set in stone. He doesn’t have the thread of his art.

“Surgery is the new sex” is the film’s signature Cronenberg line. It’s what “Long live the new flesh” was to Videodrome. The invocation of the “new flesh” as something like a regime serves to depict the film’s conflicting cult interests in media and mutilation as all-encompassing, casting both hope and doom over the proceedings, giving them weight. In Dead Ringers, in an exchange not nearly as famous but just as essential to an understanding of Cronenberg’s self reckoning, one character responds to a comment that something is “so cold and empty” with “You can call it empty, or you can call it clean”. In that line, Cronenberg puts forth two options as to how one could view his films, not commenting, simply presenting them: his off-putting sterility could be for shock value, or it could be in service of a point about the sterility itself. The slogans of Cronenberg’s work have meaning; they worm their way into your mind, and they stick because of their resonance. “Surgery is the new sex” was designated as such before the film’s release, from its appearance in the trailers, before meaning could be adequately ascribed to it. We consume our media beforehand. Knowledge of Cronenberg’s prior work helps for context, for instance, alignment of the two concepts in films such as Crash and eXistenZ might help you to figure out what it means. So the phrase caught on, and in its actual application in the film, it’s fitting that it did. Spoken, again, by Stewart’s Timlin, the line comes to signify a deep personal response to Tenser’s surgical art that builds yet another example of weight he finds himself carrying. It’s also a commentary on Cronenberg’s own repeated depictions of mutilation, and how he has occasionally tended to present them as erotically charged (see, again, his Crash). This, like the Dead Ringers line, seeks to interrogate how we feel about these concepts. Cronenberg has always been invested in the concepts behind what he presents more than the presentation itself, which is of course, what has caught on. In one scene, Tenser views the performance of another body-based artist, the “Ear Man”, whose body is adorned with dozens of ears. Ear Man is suitably creepy, with sewn-shut eyes and mouth, complete with his own Cronenberg-esque slogan: the chillingly spoken “It is time to stop seeing”. Yet, as Tenser comments, the ears don’t even work. He dismisses this art, which he perceives as phony, due to its lack of functionality. Like Tenser, Cronenberg distinguishes himself by his concern with deeper meaning. The slogan of “Surgery is the new sex” prompts Tenser to ask Timlin why it’s necessary for anything to be “the new sex”. She responds simply, saying “It’s time”.

Crimes of the Future is, in a sense, Cronenberg taking back his own signifiers, coming to terms with what they mean to him rather than how they play to audiences. The movement of time was necessary to reach this point, this film could not have existed earlier. After spending so long away from body horror, mutations and mutilations of the flesh, his ideas have of course evolved. The world has evolved with them. These parallel evolutions are, in a Cronenbergian sense of fluid reality, mutations themselves: in The Fly, the central transformations are rapid, and in Crimes, they have slowed down to keep pace with natural human evolution. Is the implication that they’ve been happening to all of us since before we realized it? In this re-contextualization of what his signature transformations really mean, Cronenberg suggests just one of many late-career advances in his work’s philosophy. The more significant revelation in the film, however, concerns the work itself. The body horror of Cronenberg’s films has always teetered between something he’s been frightened by and enamored with, this unresolved internal tension part of what makes him so fascinating. By the film’s end, Tenser, who has resisted the more fringe political readings of his artistry, finds himself fascinated by them. In the final moments, he makes a move to break free from the rigid, mechanical structures he has let govern his life and embraces the philosophy of the plastic-eaters. In the last shot of the film, Mortensen’s face turns to elation, to release, for the first time in the film. His performance is a tormented one, pulled apart by surrounding forces externally and by the renegade forces of his own body internally. He never rests: he plays sleep as painful, and it’s no coincidence Cronenberg uses sleep as the state where he develops his art. Yet in that final image, he is at peace. He has made a truly independent choice for the first time that we see, and that choice is to give in to what his body wants, correct from the course of removal, and learn to love his evolution.

David Cronenberg has already announced his next film, The Shrouds, which is set to reunite him with Eastern Promises standout Vincent Cassel. From the available plotline, the film looks like it will center on ideas of death and the line between the living and the dead. Auteur filmmakers such as Cronenberg often tend to make late-career works fascinated with such themes, reusing motifs and images from their prior work to reach a uniting personal statement. Crimes of the Future certainly qualifies as that. In finishing the film with Saul Tenser’s moment of catharsis, Cronenberg seems to be justifying his return by delighting in the next step of his personal evolution. If the original Crimes of the Future was the work of a fledgling artist who had not yet found himself, the latest Crimes of the Future is the work of an artist who has reached not only maturity, but a final understanding of what he has been working towards. It is the beginning of some sort of end, yes, but it is also, in true Cronenberg fashion, an evolution of its own. An evolution he is more than happy to embrace.