You wouldn’t be crazy to assume that Martin Scorsese’s latest foray into the world of organized crime, a world practically synonymous with the man at this point, would be a lot like his previous such efforts, such as Goodfellas, Casino, and The Departed. Those films are all fast-paced, exciting, relentlessly entertaining, universally appealing (well, except for Casino, which isn’t very good but maybe needs a rewatch. I addressed this in my Scorsese ranking article, which has been updated to include this film). The Irishman, while on the surface the same sort of movie as those, strikes a very different tone. And it does it masterfully, as great as the legendary director has been in a long time.

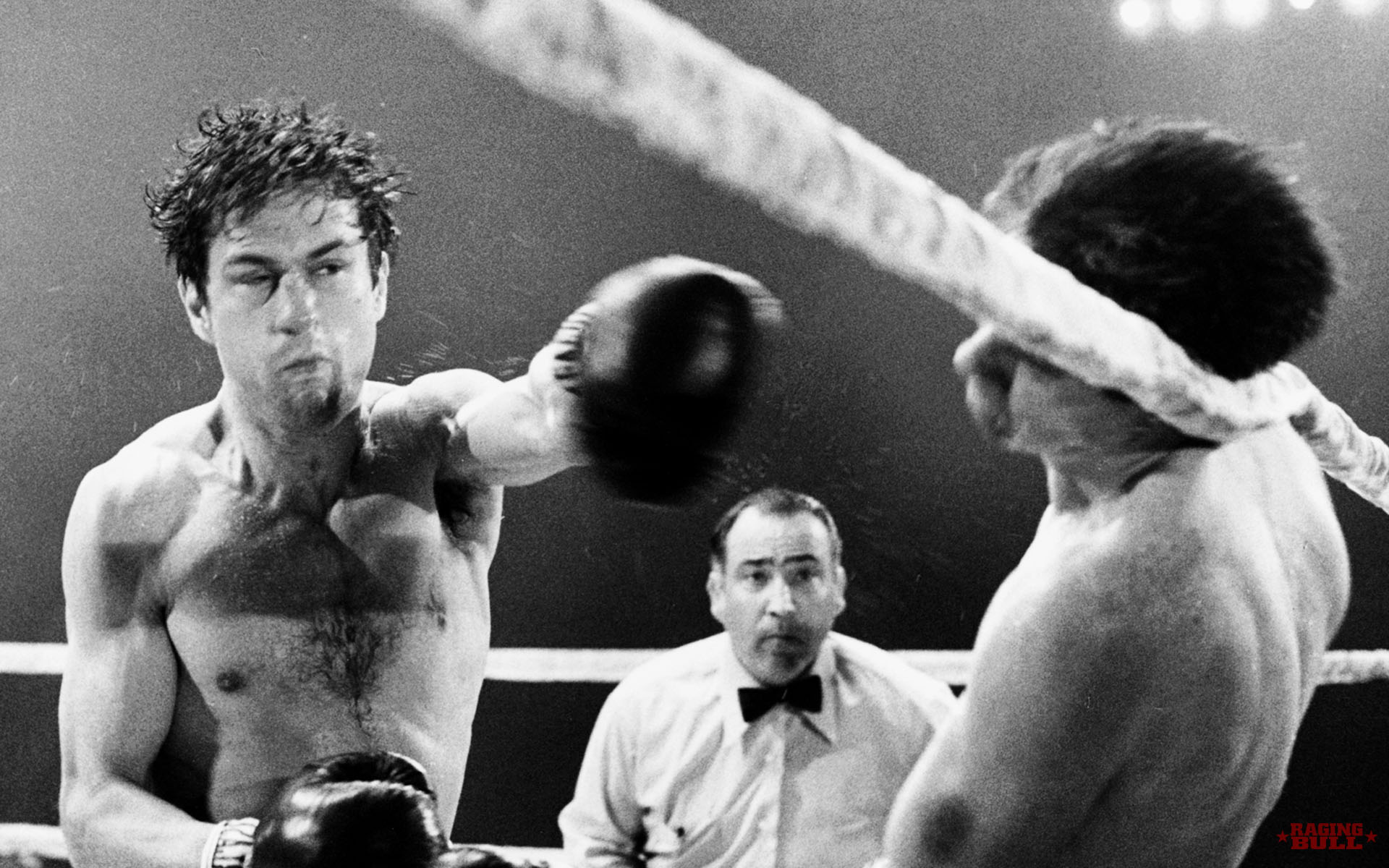

Let’s start with where The Irishman is the same as Scorsese’s prior gangster efforts. Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci are here, with both of them giving stunning and haunting performances (although the MVP of the film has yet to come). The film spans decades, is accompanied by voiceover narration, and contains lots and lots of violence. As you probably already know, it’s of certifiably epic length (3 and a half hours), which is a category none of its counterparts can touch it in. But that’s where the similarities pretty much end. The Irishman eliminates the atmosphere of excitement and action that defines Goodfellas and The Departed and the like. Instead, we’re treated to a mood of quiet reflection and the overarching theme of aging. In that sense, The Irishman isn’t a story about gangsters rising to and falling from grace, it’s a story about humans coming to terms with their own mortality and whether or not the lives they led were worth it.

The film opens with a tracking shot through the halls of a retirement home. The camera lands on Frank Sheeran (De Niro), who begins to recount a road trip he and crime boss Russell Buffalino (Pesci) took to a wedding. From the road trip framing device, we enter the story of Sheeran’s youth, and how he got acquainted with Buffalino. It began when he started allowing the meat truck he drove to be hijacked by mobsters, a charge he beat with the help of mob lawyer Bill Buffalino (a shockingly good Ray Romano). Bill introduces him to his cousin, Russell, who takes an interest in Sheeran immediately. Frank begins to take care of things for Buffalino and the mob, including several notable hits. Frank continues to rise in Buffalino’s opinion, while he also becomes more enamored with the mob lifestyle. In a critical early scene, Frank finds out his daughter, Peggy (Lucy Gallina as a child, Anna Paquin as an adult), has been hit by a grocer. Frank makes Peggy come and watch as he brutally beats the man, which visibly shakes Peggy. This begins a complicated relationship between the two of them that adds immeasurably to the film.

Frank’s relationship with Russell eventually results in his recommendation to take on the position of a bodyguard of sorts to Jimmy Hoffa. Hoffa is played by Al Pacino, who owns the thing from the moment he shows up. It’s a brilliant performance, equal parts typical recent-Pacino shouting and nuanced acting that’s better than he’s been in decades. His Hoffa is a creation of pure charisma without whom the film probably wouldn’t work.

Hoffa also strikes up a great relationship with Frank’s daughter Peggy- she’s closer to him than she is to her father (and much closer than she is with Russell, who she detests, despite her father’s protests). Hoffa takes complete control of the rest of the film, offering up some of its best moments, such as his nonchalant reaction to JFK’s assassination and his subsequent refusal to fly the flag atop the International Brotherhood of Teamsters headquarters at half mast. His confrontation with Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano (Stephen Graham, also excellent) will ensure you’re never late for a meeting (well, maybe a little late, if you account for traffic).

Frank, meanwhile, embarks on what has been (accurately) described as something of a mobster Forrest Gump. He’s present at several important moments in mafia history, claiming responsibility for notable killings such as that of “Crazy Joe” Gallo. De Niro plays these moments with alternating coolness and bravado that a lesser actor wouldn’t be able to muster at this point in their career. Pesci, meanwhile, is silent but deadly, in a role that could be considered against type due to his subdued nature. The film rolls along with typical Scorsese-an flourishes; for instance, at nearly every introduction of a minor character, a block of text appears with their name and the date and cause of their death. It’s funny, trust me. The de-aging effects don’t intrude at all, and while they may not be as effective as they should be, they get the job done.

So, if you have not yet seen The Irishman, maybe duck out here. I personally don’t think it matters all that much, but it’s your call and if I were in your position I’d probably stop reading. Your call. You’ve been warned.

The climactic event of the film is Frank’s killing of Hoffa, who, up to that point, had been maybe his closest friend. It’s built up to masterfully: Pesci turns his quiet demeanor into a frightening weapon to make it clear to Frank that he has no choice in the matter. Jesse Plemons fields unimportant questions about the logistics of a fish he transported in the back seat of his car recently (again, you have to trust me that it’s funny. Unless you’ve seen the film, in which case you know how funny it is). And then they’re alone. Frank and Jimmy walk into a house- we know what’s about to happen, Frank knows what’s about to happen, Hoffa is clueless. They enter, Hoffa sees it’s empty (a brilliant visual reference to Tommy’s whacking in Goodfellas, by the way), and he turns to leave. Frank shoots him twice in the back of the head.

The scene is heartbreaking for two reasons. The first is De Niro- Frank performs the killing with such resignation. He doesn’t hesitate for a second, he doesn’t try to say any last words to his friend, he just shoots him, like it’s business. Because, of course, it is. The second is Pacino. His portrayal of Hoffa is so masterful until the bitter end. His realization of his fate is accompanied by the directive to Frank that they should get out of there. It’s delivered in a perfect way- he can’t believe that his friend would do this to him, he doesn’t believe that he would, but yet it’s the only rational explanation. In Pacino’s voice, you can detect a sliver of doubt, of the thought that maybe Frank would turn on him. But mainly he really believes that Frank’s leaving with him, and that he’s leaving at all. It’s a masterclass in one line, and it’s a perfect finale to an epic performance.

After Hoffa’s killing, Frank’s relationship with Peggy ends. Of course, he doesn’t admit the crime to anyone, even comforting Hoffa’s wife (Welker White, superstitious babysitter Lois Byrd in Goodfellas) and telling her that he’ll turn up at some point. Oscar winner Anna Paquin notably doesn’t speak at all in her role as adult Peggy, save for in one scene (and even then, barely). She simply asks her father why he hasn’t called Hoffa’s wife yet. It’s a seemingly simple question, but everything about it- Paquin’s delivery, the emphasis on the character’s silence throughout the film- suggests that she knows exactly why. She knows what her father has done for a living for decades, and she knows that killing Hoffa is absolutely something he could’ve been ordered to do. There’s clearly no doubt in her mind that he did it. Despite this being the only scene in the film where she speaks, the character of Peggy is an essential one. Throughout, she casts knowing glances at her father, expressing emotions of deep anguish and sorrow at his intrinsic violence. His lifestyle fundamentally upsets her, and so she fears him. Yet she loves Hoffa. She has from her childhood, when he was the only one of Frank’s friends she would talk to, and to her adulthood, when she dances with him multiple times at a dinner honoring Frank. The camera focuses on her often, as if to exemplify her silent, contemptuous stares and her joy at Hoffa’s presence. It’s through Peggy that Frank realizes that what he’s done is wrong, and only after he loses her that he starts to look back and regret.

The ending of The Irishman echoes the endings of other Scorsese gangster films in a fascinating way. The film concludes with an elderly Frank Sheeran, alone in a nursing home, presumably on his last night alive. He asks the visiting priest if, on his way out, he could leave the door slightly open. The final shot is of Sheeran, sitting alone, viewed through the crack in the doorway. By this point, all of his friends and associates are dead, he’s been abandoned by his daughter, and he has nothing left. The message here is a new, and much darker, one for Scorsese. At the end of Goodfellas, Henry Hill laments the fact that he’s had to leave behind life in the mob, that he has to “live the rest of his life like a schnook”. Casino finishes with Ace Rothstein musing that Las Vegas isn’t what it used to be, comparing it to an adult version of Disneyland. Both of these men, Hill and Rothstein, miss their ideals of the Good Old Days, including the bloodshed that came with them. In The Irishman, Sheeran doesn’t look back on his past with fondness or loss, his overwhelming emotion is regret. The finale of the film, detailing Sheeran’s elderly life, drives this point home- that Frank regrets it all. He regrets his alienation of his daughter Peggy, he regrets the killing of his friend, he regrets all of his life choices. The difference between Frank’s perspective and those of Hill and Rothstein is that the latter two had merely finished their careers in the mob. Sheeran is at the end of his life. This perspective allows him to see the futility of it all. And that’s the takeaway from The Irishman: no matter who you are, and how you lived, it won’t matter once you get to the end. While Scorsese certainly hasn’t come to the end, of his career or his life, his observation gives his film a profound depth that he hasn’t achieved in his past similar work. That’s what makes The Irishman so different, and that’s what makes it so great.

Score: 5/5

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13167865/king_of_comedy.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65412061/irishman3.0.jpg)