Social distancing has allowed for quite a bit of down time for movie watching, which I have so far taken ample advantage of. So far I have watched 38 films for the first time, rewatched others, and on occasion rewatched some of my first time watches because they’re just that good. However fleeting it is, movies have been a welcome distraction from the outside world, even if some of them end up being more timely than I anticipated (looking at you, The Host). I have every intention to make this list outdated in short order, as with nowhere to go, my movie watching seems unlikely to stop. But for now, here’s the 20 best things I’ve watched so far, ranked (could they be presented any other way?)

20- A Day in the Country (Jean Renoir, 1936)

French master Jean Renoir’s 40-minute mini-film is one of his most beloved works with good reason. It hits the atmosphere he works best in with an ease that fits its slight structure and allows it to glide along leisurely. It’s peaceful and utterly delightful, until Renoir’s typical emotional melodrama mixed with social commentary comes in and ends the thing on a melancholic note that emphasizes all that came before it. Does it feel somewhat lesser than his towering, feature length masterworks Grand Illusion and The Rules of the Game? Yes. Is it still worthwhile? Yes.

19- Modern Times (Charlie Chaplin, 1936)

The second Chaplin film I’ve seen, after City Lights. While it isn’t quite as great as that film, it has a lot to recommend it: it’s funnier, for one, and it feels genuinely relevant today in its critique of industrialized society. It also has the honor of being used in Joker so that Todd Philips can prove how much he knows about cinema while he cruises along at the helm of one of the greatest affronts to the medium in recent memory. Modern Times is a wonderful film that doesn’t deserve permanent association with Philips’ disasterpiece. If that film causes people to go seek out Modern Times, it will have left at least one good thing in its vile wake, as Modern Times is an essential and deeply enjoyable work of early Hollywood, and one that represents such an important place in cinematic history that it should be mandatory viewing for anyone interested in the history of film.

18- What’s Up, Doc? (Peter Bogdanovich, 1972)

Although it’s wildly enjoyable up until this point, what really sold me on What’s Up, Doc? was the ending. In it, Ryan O’Neal of Love Story fame (although his best work is in Barry Lyndon) is confronted with his iconic “love means never having to say you’re sorry” line from that film, and replies with “That’s the dumbest thing I ever heard”. To me, this was one of the great endings in screen history. For, you see, it is a REMARKABLY stupid line, and having the man who became famous off of it disavow it as such only two years later was not only a perfect cap to the movie’s winking sensibilities, but also an affirmation of the fact that it’s one of the worst lines in cinematic history. Even aside from that glorious moment, What’s Up, Doc? is utterly phenomenal. It’s hilarious, it’s entertaining, it’s extremely different. The script, written by the late great Buck Henry, is certainly one of the greatest comedic screenplays there is, and it’s sold every step of the way by stars Barbra Streisand, Madeline Kahn, and O’Neal. This is a weird movie that enjoys its own weirdness to the extent that it doesn’t really care if the viewer does too, and in doing so it reaches a charming and fascinating point where you can’t help but be entranced by it.

17- Hour of the Wolf (Ingmar Bergman, 1968)

Part of a (rather depressing) Bergman streak in my viewing was the master’s only horror film, and oh my god did he make the most of it. Hour of the Wolf is INSANE. It throws whatever gonzo imagery it can think of at a wall in the hope that some of it will stick, and all of it does. It all blends together in a maelstrom of discomfort and mounting dread that both stands out among Bergman’s filmography and encapsulates the dark perversions that run through his work. It’s one of his masterpieces, inhabiting the second tier of his films among stuff like The Seventh Seal and Cries and Whispers. This is the tier of films that are clearly masterpieces, but not at the same level as stuff on tier one: Wild Strawberries and Persona, both of which have cases to be made for the title of greatest film ever made. Ending the random diversion on my Bergman tiering and getting back to the movie at hand- Hour of the Wolf is a unique experience. It feels like a Bergman film refracted through the very essence of nightmares, calling to the forefront the darkest parts of the human being only hinted at in his other work. It’s unhinged, and it serves as more of a manifesto for the man’s work than anything this different from the rest of it should.

16- Zelig (Woody Allen, 1983)

Zelig takes the form of a mockumentary about “human chameleon” Leonard Zelig, a man who becomes internationally famous in the late 1920s for his ability to essentially shapeshift to mimic whoever he’s around. The concept allows Allen to let loose on the jokes (“As a boy, Leonard is frequently bullied by anti-semites. His parents, who never take his part and blame him for everything, side with the anti-semites”) as well as wax philosophical about identity and conformity. But the real star, almost to a fault, is the satire of jazz age American life. A lot of time is spent on depictions of late-20s society: musical breaks set to invented songs, winking references to stars of the time, et cetera. The film fully commits to the bit, never straying an inch from the faux-documentary style, impressively fitting comedy and storytelling in without ever feeling like it’s trying to do too much. It’s upper level Allen, an intriguing concept that delivers on its potential.

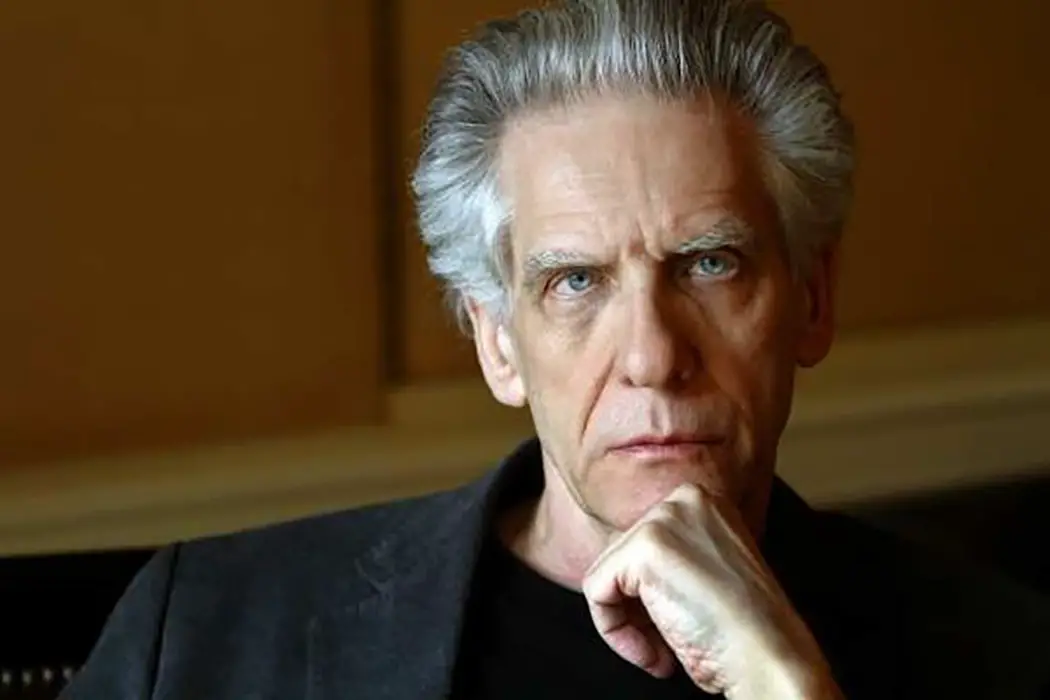

15- Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983)

Quite possibly the quintessential Cronenberg. Packed to the brim with body horror, supremely nasty visuals, and, of course, liberal use of the word “flesh”, Videodrome feels like Cronenberg’s mission statement, a perfect encapsulation of the fascinations that define his work. Is it as good as The Fly or Eastern Promises? No it is not, but it cuts to the heart of his recurring themes and ideas in a way that would likely be off-putting to uninitiated viewers but is utterly joyous for fans. It’s all here, from the association of humanity and live flesh to a dark commentary on how the screen eliminates these things. On the surface Videodrome is a gross-out b-movie, but lurking under the seedy surface is an unbelievable bounty of thematic riches. One of my all-time favorite films to analyze, to the point where I might end up doing a whole post on it.

14- Faces (John Cassavetes, 1968)

John Cassavetes’ legendary film Faces is… not exactly a fun watch. Paced with extreme deliberation and shot through with a rejection of cinematic aspects in favor of a more vérité approach, Faces parks you in front of deteriorating people and makes you watch them crumble for over two hours. In total, across the 130 minute runtime, there are like 10 scenes (this is probably not a fully accurate figure but it is not a high number). The focus is entirely on the actors, all of whom turn in brilliant performances: Lynn Carlin (who earned an Oscar nomination for the film), John Marley (of Jack Woltz from The Godfather fame), and Cassavetes regulars Gena Rowlands and Seymour Cassel. This is a raw film, a grueling experience, a difficult sit, and that’s the whole point. Cassavetes wants this to hurt, because he wants the viewer to fully empathize with the ailing characters. He wants this to feel hard to get through, because in doing so he avoids the aspect of escapism inherent to film. This is designed specifically to stay with and continually needle the viewer, and it works. It’s an astonishing achievement (although The Killing of a Chinese Bookie remains my Cassavetes of choice.)

13- The Fugitive (Andrew Davis, 1993)

Faces may not be the most fun thing to watch, but do you know what is? The Fugitive. This movie is, in the truest, most primordial sense of the word, awesome. Proof that a movie can be ridiculously entertaining as well as a truly great film, this boasts: career performances from Harrison Ford and Tommy Lee Jones, brilliant action set pieces, weirdly high billing for a one-scene Julianne Moore performance, and an all-time delivery of the line “I don’t care”. What more could you possibly ask for, besides one of the best John Mulaney bits and an appearance from Joe Pantoliano, aka Ralphie from the Sopranos, both of which this movie also has. You know what, I’m out of interesting ways to integrate it into paragraph format, so here’s a bulleted list of stuff that owns about The Fugitive.

- The fact that it’s so good that it earned a best picture nomination alongside Schindler’s List despite its status as a lowly action thriller

- Jeroen Krabbe’s accent

- The brilliantly constructed opening sequence

- James Newton Howard’s score

- Director Andrew Davis, who went on to make the film adaptation of Louis Sachar’s Holes that’s burned into my memory for some reason. The cast for that movie is insane. Beyond the likes of Shia LaBeouf, Sigourney Weaver, Jon Voight, Patricia Arquette, Henry Winkler, and Tim Blake Nelson, there’s some cool names in here. Basketball player Rick Fox. Ken Davitian, aka Azamat Bagatov in Borat. Wild.

- Harrison Ford’s beard

12- Deep Red (Dario Argento, 1975)

GAHH LOOK AT THAT THING. Deep Red (also known by its cool-ass Italian title Profondo Rosso) was my introduction to the, uh… let’s say flamboyant stylings of giallo god Dario Argento (although it is not his highest film on this list). It’s a shock to the system, a totally original work that manages to toe the line between ridiculous and serious by not caring about “rules” and rushing headlong into both sides simultaneously. It’s fully aware of its comical absurdity, and instead of making a point of pointing it out or trying to minimize it, the film simply lets it happen while also going off in another direction. It’s not really all that scary (although the scene with the above horrifying baby thing did make me jump), but it’s fun, and it’s hard not to get caught up in the wild tone.

11- Black Narcissus (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1947)

Black Narcissus takes you up into the mountains with its characters and invites you to spiral out of control with them in real time. The progression from run of the mill drama to psychological horror is pulled off with astounding control by one of the greatest filmmaking duos to ever do it. The sense of atmosphere in the film really kicks in during the darker (and better) second half, which reaches points where it feels like you’re watching something almost as good as The Red Shoes (it isn’t, nor is it all that close, but there are moments of the same level of unbelievable mastery). Jack Cardiff’s cinematography is at its best, elevating the locale of the mountains to the mythic context it requires. It leaves you wondering how they pulled off something this audacious in 1947. The answer is simple: Powell and Pressburger didn’t care about what was possible in their time, they simply did what they wanted.

10- Phantom Thread (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2017)

Is Paul Thomas Anderson just incapable of making movies that aren’t masterpieces? Sure, having maybe the most talented actor of all time in Daniel Day-Lewis helps, but the pieces all come together around him immaculately. Vicky Krieps holds her own against DDL the entire way, and Lesley Manville’s chilly presence is so damn fun to watch. Yeah, this could’ve very easily been your average stuffy period drama, but in the hands of one of the all-time great talents it’s livelier and more contemporary than it has any right to be. Best of all, it’s weird. It’s weird as hell, weirder than any other period piece would dare to be. One of the most daring and original films of the last couple of years, hiding under the facade of something that’s been done a thousand times before. There’s a lot that’s fitting about that. At its core, Phantom Thread is about the disparity between inner and outer beauty, so it’s fitting that it’s so much more than meets the eye. Plus it’s funny as hell. Day-Lewis looking at the dress he’s designed and remarking “It’s just not very good, is it?” before doubling over is the absolute height of comedy.

9- Dawn of the Dead (George Romero, 1978)

Hot take: this is miles better than the classic original Night of the Living Dead. That film isn’t without the aspects that make it deserving of its legendary status, but it never really comes together like this does. Dawn is more polished, more thought-out, and much wider in scale, a transition that’s handled wonderfully. Dawn addresses the wider societal consequences of a zombie apocalypse in fascinating ways, and also goes further into the individual toll it takes. The mall as a setting is utilized brilliantly, contributing to the world-building that makes this movie special while also providing an excellent theater for the suspense needed to propel the story. This is fleshed out in ways never hinted at by the original, and it makes the most of all of its ideas. Absolutely brilliant.

8- The Evil Dead Trilogy (Sam Raimi, 1981, 1987, 1992)

This isn’t cheating, because the title of the post says things I’ve watched during quarantine as opposed to movies. So it’s allowed. Anyway, the Evil Dead trilogy is one of the defining events of the lockdown for me, to the point where I subscribed to a free trial to my sworn nemesis quibi because I found out that they’re doing a show by Sam Raimi (it’s pretty good). The films follow the oddest trajectory of any franchise: the first film, 1981’s The Evil Dead is a straight horror movie and the third, Army of Darkness from 1992, is a straight comedy. Bridging this seemingly impossible gap and making this seem like a natural transition is the 1987 masterpiece Evil Dead II (or Evil Dead II: Dead by Dawn if you’re a sociopath). II makes the insane hypothesis that horror-comedy equilibrium can only be achieved by smashing horror and comedy together violently until you’ve killed them both and created something horrible. This is objectively false, and yet by the end of 84 swaggering, bravura minutes the film has proven it true. It’s one of the most ridiculously well-made movies there is, fully selling you on its own insanity by amplifying that insanity to the point where it’s so ridiculous that it exists in its own plane of logic, one in which it somehow becomes rational. The remarkably assured confidence of Raimi and star Bruce Campbell persist throughout the whole trilogy, but here they invent an entire new cinematic language that sustains their escapades. The other two films are incredible as well, but not to the same extent. The trilogy is one of the greatest out there, and if it isn’t the best, it’s certainly the grooviest. Hail to the king, baby.

7- All that Heaven Allows (Douglas Sirk, 1955)

On paper, All That Heaven Allows doesn’t work. It’s an overly moralistic parable about high society life in which Rock Hudson talks about trees a lot and most of the emotional turns are telegraphed. But it’s elevated to masterpiece status by Sirk and lead actress Jane Wyman, who provides the perfect subtle contrast to the obviousness of the cast of characters around her. The technicolor cinematography is terrific, and it really does manage to earn an emotional investment. Hudson’s performance turned me off a bit at first but I eventually came around to the character’s idiosyncrasies and he wound up oakay with me (when I say he talks about trees a lot I mean a lot). I watched this on a whim and was shocked by how much I loved it, and am now more so by how much it clearly stands as one of the best things I’ve seen during this whole thing.

6- Cries and Whispers (Ingmar Bergman, 1972)

Quite possibly the most oppressively depressing movie ever made, Cries and Whispers would give ample ammunition to anyone looking to prove stereotypes of Bergman’s self-seriousness. But it’s also commonly held up as one of his best films, which is because it is one of his best films. It’s not exactly a lot of fun, but it’s haunting and devastating in the way that his very best stuff is. Sven Nykvist makes brilliant use of color cinematography, using the red color motif in ways that don’t fully pay off until the unforgettable final scene, when the absence of the color in favor of white serves to jar the viewer. Cries and Whispers is full of jarring moments, some in subtle ways like that in some in more aggressive ways. This is Bergman working through some stuff, and it shows not only in the content but in the quality of the finished product. This and The Exorcist were in the same Oscars best picture lineup. The fact that they were both nominated is one of the Oscars’ great triumphs, the fact that neither won is one of their great failures.

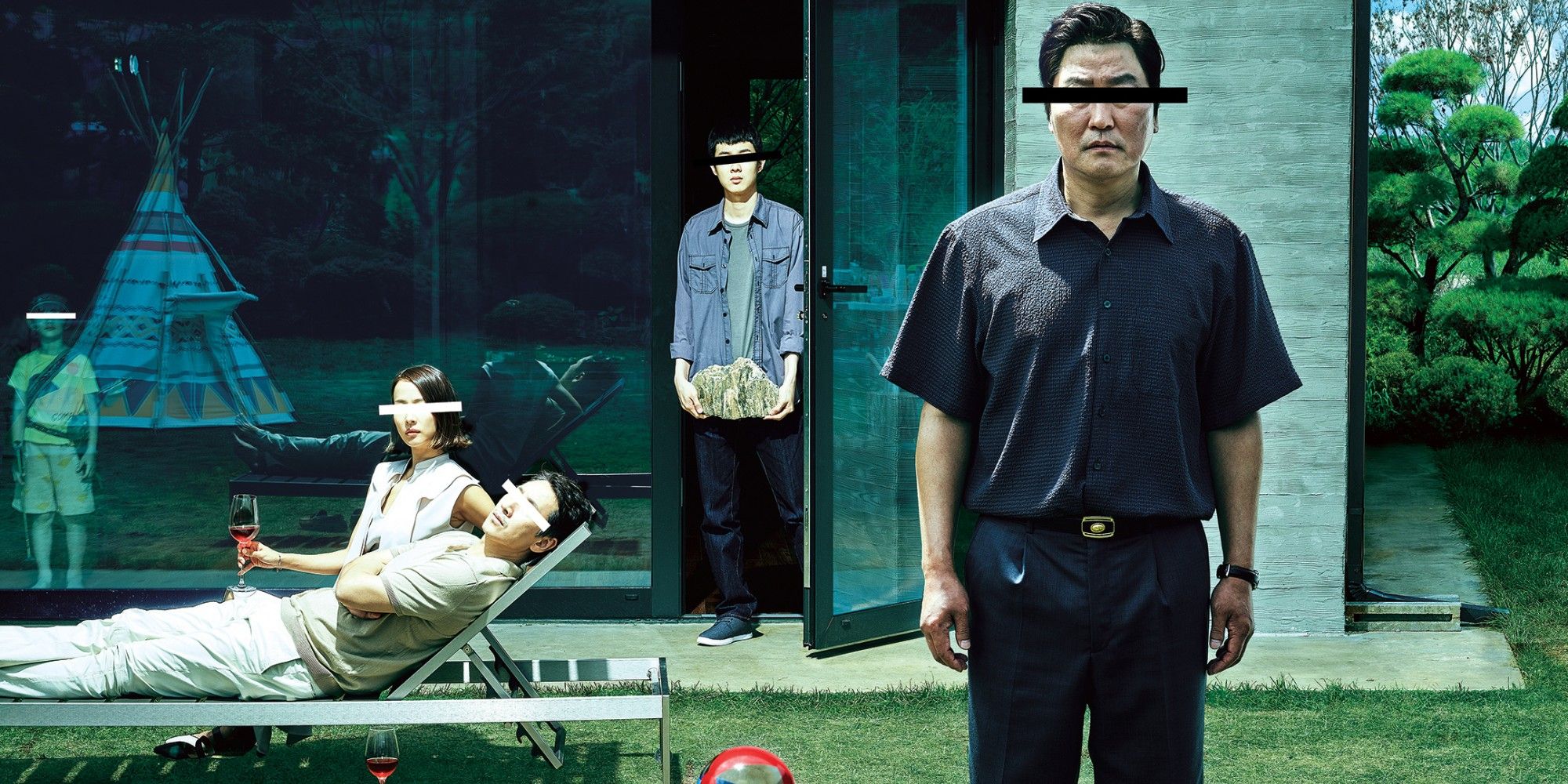

5- The Host (Bong Joon-Ho, 2006)

Who else but Bong Joon-Ho could take this ridiculous monster movie concept and make it so devastating, so angry, so funny, and still so totally in tune with its underlying ridiculousness? The Host is fun, it’s frightening, it’s intense, it’s a marvel of construction and a miracle of confident filmmaking. It’s everything Bong’s best work is, which makes it something special. Watching Bong at his best, like this, makes me wonder why I ever watch anything else. The scene of the first monster attack is one of the greatest things ever filmed: the initial approach of the beast has the kind of surreal levity that makes it seem like a genuine scene from a nightmare. Fans of Parasite should definitely check this one out.

4- Suspiria (Dario Argento, 1977)

This movie is unfair. Argento blatantly violates every common sense rule of filmmaking and produces one of the greatest films, not only in the horror genre, but in history. Who says you have to actually have a story? Why on earth do you actually have to have things happen to progress your plot? Suspiria is basically just bright red lighting and cinema’s greatest score (which barely qualifies as music, I think) combining to create a mood piece that aggressively resists any attempts to conform to something other than its overarching vibe. Calling it an experience rather than a film feels pretentious and cliched, but it’s true. This is something that happens to you rather than something that you watch. Who cares if any of it makes any sense? Just go with it and you’ll be rewarded.

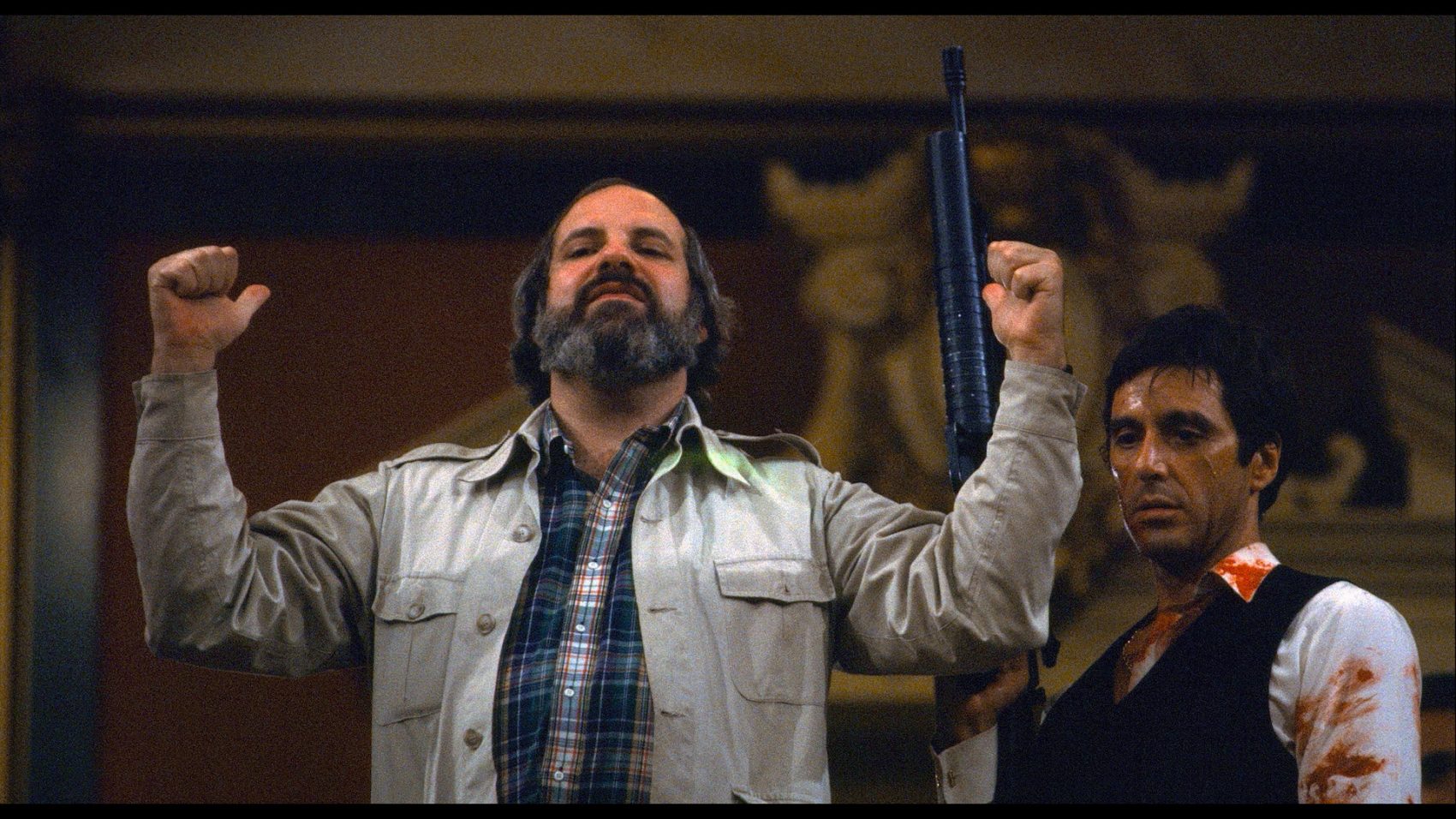

3- Phantom of the Paradise (Brian de Palma, 1974)

How does one describe Phantom of the Paradise? Wikipedia calls it a “musical rock opera horror comedy film”, which is actually pretty good, but doesn’t really go all the way in explaining the full extent of the insanity at play here. Phantom takes elements of Faust, Phantom of the Opera, and The Picture of Dorian Gray, blends them all up into the already existing genre smoothie listed above, drinks it, and then does like a half a pound of cocaine. The result is glorious, an instant personal favorite from the minute the credits rolled. I watched it again the next day, something I never do, simply out of a desire to make sure I didn’t dream any of it. The songs were written and composed by Paul Williams, who plays the villain and would later serve in a similar musical capacity for The Muppet Movie. So Swan is played by the guy who wrote “Rainbow Connection”. The fact that this movie exists is unbelievable. I’m obsessed with it. Easily my favorite film of this whole thing.

2- Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Celine Sciamma, 2019)

I remain at a loss for the words with which to describe this movie. I genuinely can’t do it. Its greatness is so obvious yet so intangible. It feels like a magic trick, like hypnosis. You’re lured in by the astonishing visuals and brilliant acting and you just watch, not even fully comprehending any of it until the ending. Then you walk away in a daze, unable to shake it. It’s the feeling of seeing one of the greatest films you’ll ever see.

1- High and Low (Akira Kurosawa)

High and Low isn’t one of Kurosawa’s most well known films outside of dedicated cinephile circles. It isn’t mentioned with the same frequency as the likes of Seven Samurai and Rashomon. It isn’t as influential as The Hidden Fortress or Yojimbo. But ask any of its devotees, and they’ll tell you that it’s among his very best. Everything here works towards the film’s purpose, every narrative beat has weight. Every single shot is a work of art, with Kurosawa positioning his characters in innovative ways to maximize the single setting location of the first half. It implements a revolutionary structure: there are two distinct halves with three acts each. Toshiro Mifune does what very well may be his career best work, which is saying a lot. It all clicks together perfectly, the commentary, the entertainment, the cinematic value. Clearly one of the greatest films ever made, and its meticulous brilliance appears to have been pulled off with ease. High and Low is something truly special, and pound for pound it’s the best thing I’ve watched all quarantine.